Touchdown short of runway

Air Inuit Ltd.

Boeing of Canada Ltd. de Havilland Division DHC-8-314, C-GAIW

Kangiqsujuaq (Wakeham Bay) Airport (CYKG), Quebec

The Transportation Safety Board of Canada (TSB) investigated this occurrence for the purpose of advancing transportation safety. It is not the function of the Board to assign fault or determine civil or criminal liability. This report is not created for use in the context of legal, disciplinary or other proceedings. See Ownership and use of content. Masculine pronouns and position titles may be used to signify all genders to comply with the Canadian Transportation Accident Investigation and Safety Board Act (S.C. 1989, c. 3).

Summary

On 30 March 2024, at 1352 Eastern Daylight Time, the Boeing of Canada Limited de Havilland Division DHC-8-314 aircraft (registration C-GAIW, serial number 300) operated by Air Inuit Ltd. took off from La Grande Rivière Airport (CYGL), Quebec, to conduct a daytime cargo flight under instrument flight rules to Kangiqsujuaq (Wakeham Bay) Airport (CYKG), Quebec, with 2 flight crew members and 1 cargo agent on board. During landing, the wheels touched down slightly short of the runway, and the lower part of the left main landing gear broke off. The aircraft bounced and touched down again with only the nose wheel and right landing gear. Directional control was maintained, and the aircraft came to a stop on the runway. The aircraft sustained substantial damage to the left landing gear, fuselage, and left propeller. There were no injuries.

1.0 Factual information

1.1 History of the flight

At 1352All times are Eastern Daylight Time (Coordinated Universal Time minus 4 hours). on 30 March 2024, the Boeing of Canada Ltd. de Havilland Division DHC-8-314 aircraft (DH8C) operated by Air Inuit Ltd. (Air Inuit) took off from La Grande Rivière Airport (CYGL)All locations mentioned in this report are in the province of Quebec, unless otherwise stated. to conduct a daytime cargo flight under instrument flight rules to Kangiqsujuaq (Wakeham Bay) Airport (CYKG) (Figure 1), with 2 flight crew members and 1 cargo agent on board.

At approximately 1525, while in cruise flight bound for CYKG, the flight crew began preparing for the approach and landing. The crew obtained the weather conditions at CYKG from the Air Inuit dispatcher. The report stated that at that time, winds were from 080° true at 23 knots, visibility was ½ statute mile (SM) in light snow and blowing snow, and sky conditions were a broken ceiling at 400 feet above ground level (AGL) and an overcast cloud layer at 1800 feet AGL.

The flight crew made a plan in case the weather deteriorated and chose to conduct a pilot-monitored approach (PMA) because of the weather conditions. The flight crew then completed a PMA approach briefing for the area navigation approach using the global navigation satellite system [RNAV (GNSS)] for Runway 15 at CYKG. At 1537, the aircraft began its descent and the first officer, who was going to be the pilot flying (PF) for the PMA, took the controls shortly thereafter.

At 1542, the pilots received a weather update from the CYKG community aerodrome radio station. The winds were reported to be from 100° magnetic (M) at 24 knots, and visibility was ½ SM, with a broken ceiling at 300 feet AGL and an overcast cloud layer at 600 feet AGL.

At 1547, the aircraft was 3 nautical miles (NM) from final approach waypoint (FAWP) KEGTI, on the glide path and horizontal approach path.

At 1548, the community aerodrome radio station reported that winds were from 120°M at 24 knots.

At 1550, the aircraft crossed the FAWP with flaps at 15° and the landing gear extended. The checklists had been completed.

At 1552:09, the aircraft was on autopilot and flew above the glide path. It returned to the glide path 41 seconds later. The aircraft’s speed then stabilized at 120 knots, which was the approach speed.

At 1553:18, the aircraft crossed the approach gate while on the glide path and meeting all of Air Inuit’s requirements for a stabilized approach.

At 1553:32, the aircraft, still on autopilot, flew above the glide path a 2nd time (approximately 100 feet above). Thirteen seconds later, the PF disconnected the autopilot to manually return to the glide path.

At 1553:54, the aircraft was 1 NM from the threshold of Runway 15, with a deviation of approximately 80 feet above the glide path (1 point on the glide path indicator) at 126 knots and slightly to the left of the horizontal approach path. The captain provided the PF with some guidance to help return to the glide path and the horizontal approach path.

At 1554:04, the aircraft was 0.75 NM from the threshold, on the glide path and the horizontal approach path, and 1 second later, the decision altitude, corrected for the temperature at 780 feet above sea level (ASL), was reached. The flight crew, who had had the runway in sight for several seconds before reaching the decision altitude, continued the flight to landing.

At 1554:10, the aircraft descended below the RNAV approach’s glide path and remained below it from that point on.

At 1554:16, when the aircraft was 0.4 NM from the runway, the flaps were lowered to 35°. The captain took the controls and began reducing the speed for the landing, while the aircraft was approximately 50 feet below the RNAV approach’s glide path (a deviation of approximately 1.75 points). This deviation was maintained until touchdown as the aircraft descended on a visual approach angle of 3°.

At 1554:31, when the aircraft was approximately 450 feet from the threshold and 20 feet above the threshold elevation, its attitude changed from 2.3° to 5.5° nose up in 2 seconds.

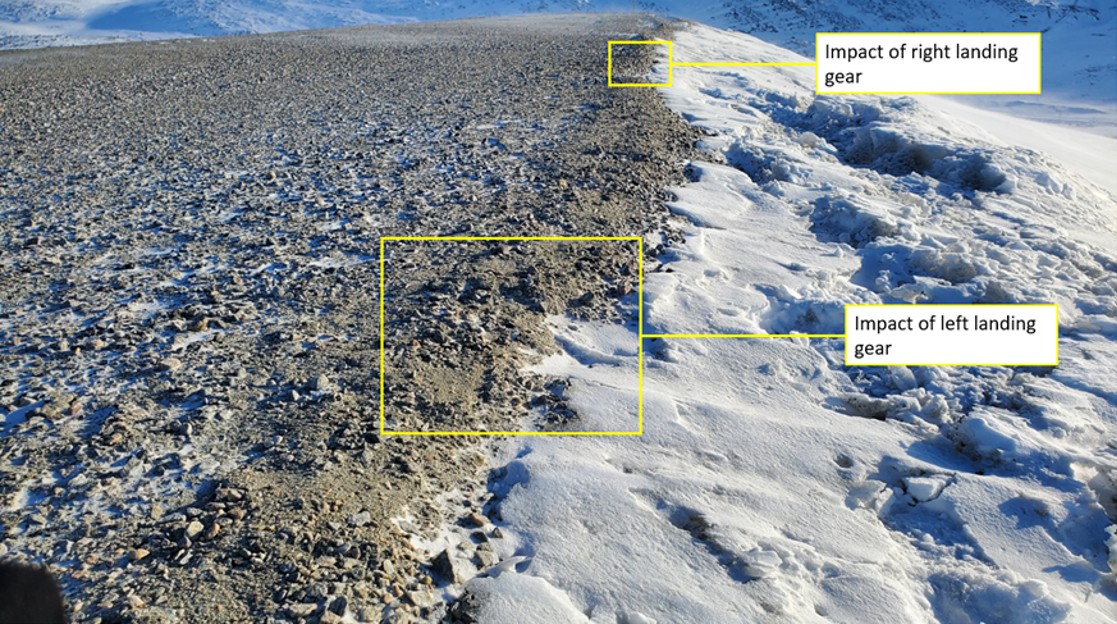

At 1554:33, the main landing gears touched down on the gravel mound that delineates the end of the runway, 220 feet before the threshold (Figure 2). The left wheel touched the ground approximately 5 inches below the runway, and the right wheel touched down approximately 4 inches below the runway.

The piston subassembly and wheels broke free from the left landing gear, unbeknownst to the flight crew. The aircraft bounced, and the captain landed the aircraft on the runway, while remaining in the centre of the runway. The aircraft came to a stop approximately 2100 feet beyond the threshold of Runway 15 (Figure 3).

1.2 Injuries to persons

There were no injuries.

1.3 Damage to aircraft

The aircraft sustained substantial damage to the left landing gear, left propeller, and left nacelle. The lower aft fuselage had damage due to friction, as well as puncture holes in the skin and dents in the structure.

1.4 Other damage

There was no other damage.

1.5 Personnel information

Captain | First officer | |

|---|---|---|

Pilot licence | Airline transport pilot licence (ATPL) | Commercial pilot licence (CPL) |

Medical expiry date | 01 January 2025 | 01 October 2024 |

Total flying hours | 10 120 | 1002 |

Flight hours on type | 3984 | 13.4 |

Flight hours in the 24 hours before the occurrence | 6.5 | 2.1 |

Flight hours in the 7 days before the occurrence | 11.5 | 7.2 |

Flight hours in the 90 days before the occurrence | 119.4 | 11.3 |

Flight hours on type in the 90 days before the occurrence | 111.9 | 11.3 |

Hours on duty before the occurrence | 8.2 | 4.7 |

Hours off duty before the work period | 12.6 | 22.5 |

The flight crew held the appropriate licences and ratings for the flight in accordance with existing regulations.

The captain had 8 years’ experience as captain on DH8C aircraft. He had been working for the airline as a pilot since 2011. His pilot proficiency check (PPC) was conducted in June 2023. His semi-annual recurrent training and the one approved as a substitute for the PPC took place in December 2023.

The first officer had been working for the airline as a pilot since January 2024. He had been assigned to DH8C aircraft and had taken initial training and successfully completed his PPC in February 2024.

1.6 Aircraft information

The occurrence aircraft is a DHC-8-314, which is a DHC-8-100 that has been extended by 11.3 feet. It had been modified to transport cargo and had 1 oversized rear cargo access door.

Manufacturer | Boeing of Canada Ltd. de Havilland Division* |

|---|---|

Type, model, and registration | DHC-8-314, C-GAIW |

Year of manufacture | 1991 |

Serial number | 300 |

Certificate of airworthiness issue date | 07 September 2016 |

Total airframe time | 44 144.9 hours |

Engine type (number of engines) | Pratt & Whitney PW123B (2) |

Propeller type (number of propellers) | Hamilton Sundstrand 14SF-23 (2) |

Maximum allowable take-off weight | 43 000 pounds (19 505 kg) |

Maximum allowable landing weight | 42 000 pounds (19 051 kg) |

Recommended fuel type(s) | Jet A, Jet A1, JP5, JP8, Jet B, JP-4 |

Fuel type used | Jet A1 |

* De Havilland Aircraft of Canada Limited currently holds the type certificate for the aircraft type.

The aircraft took off from CYGL with a weight of 42 998 pounds and landed at CYKG with an estimated weight of 40 302 pounds. The aircraft’s weight and centre of gravity were within the prescribed limits.

There were no recorded defects outstanding, nor were any defects reported by the crew at the time of the occurrence. There was no indication that a component or system malfunction played a role in this occurrence.

1.7 Meteorological information

The aerodrome special meteorological report (SPECI) for CYKG, issued at 1546, reported the following:

- Winds from 070° true, at 24 knots

- Visibility of ½ SM in snow and blowing snow

- Broken ceiling at 300 feet AGL and overcast cloud layer at 500 feet AGL

- Temperature −4 °C and dew point −5 °C

- Altimeter setting 29.81 inches of mercury (inHg)

Approximately 6 minutes before landing (i.e., 2 minutes after the SPECI report above), winds were reported to be from 120°M at 24 knots.

1.7.1 Downdrafts

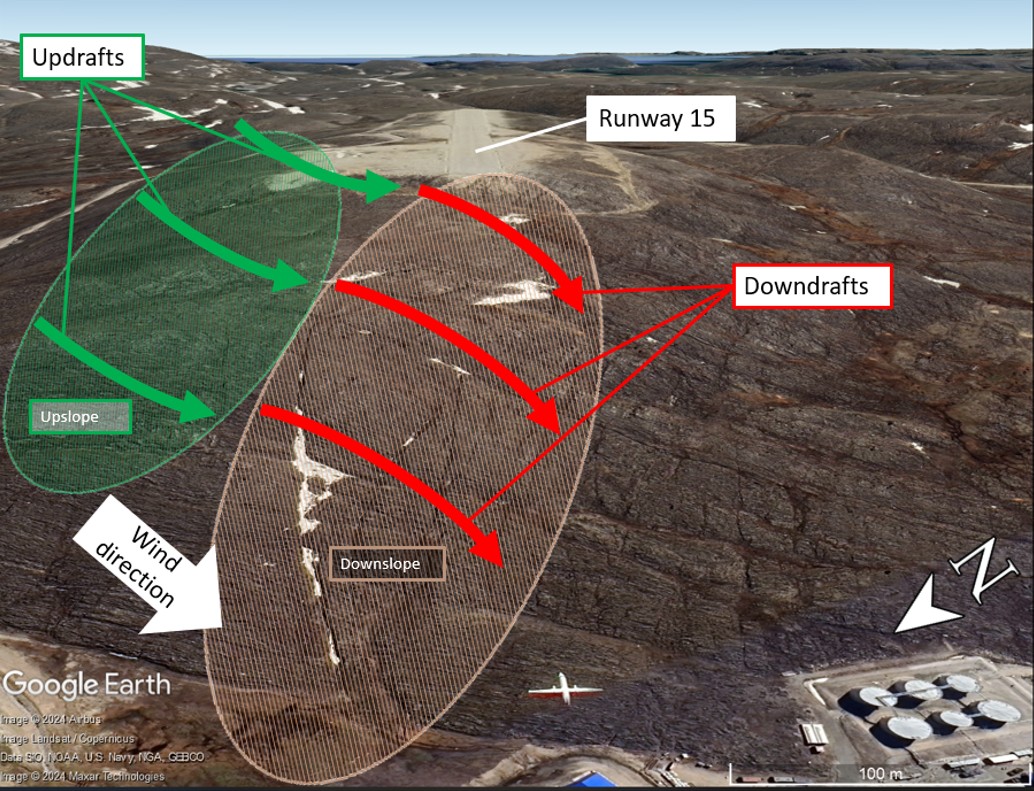

CYKG is in an area that is characterized by rocky, uneven terrain. Vegetation is sparse in the area around the airport, which sits on a rocky hill near the small coastal village of Kangiqsujuaq.

The publication AWARE provides a detailed explanation of wind effects in mountainous terrain:

When the unstable air moves over a mountain peak, which acts as a barrier, it then flows downward often in the form of relatively violent downdrafts. The speed of the descending air can sometimes exceed an aircraft’s climbing ability, and cause a collision with the underfeature [Figure 4].Environment Canada, AWARE: The atmosphere, the weather and flying (January 2011), Section 14.3.1: Flying Over Mountainous Terrain, p. 130, at https://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2013/ec/En56-239-2011-eng.pdf (last accessed on 09 December 2025).

Taking into account the topography around CYKG and the winds present at the time of the occurrence, the investigation determined there were likely downdrafts in the final approach area for Runway 15 at that time (Figure 5).

1.8 Aids to navigation

Not applicable.

1.9 Communications

There were no known communication difficulties.

1.10 Aerodrome information

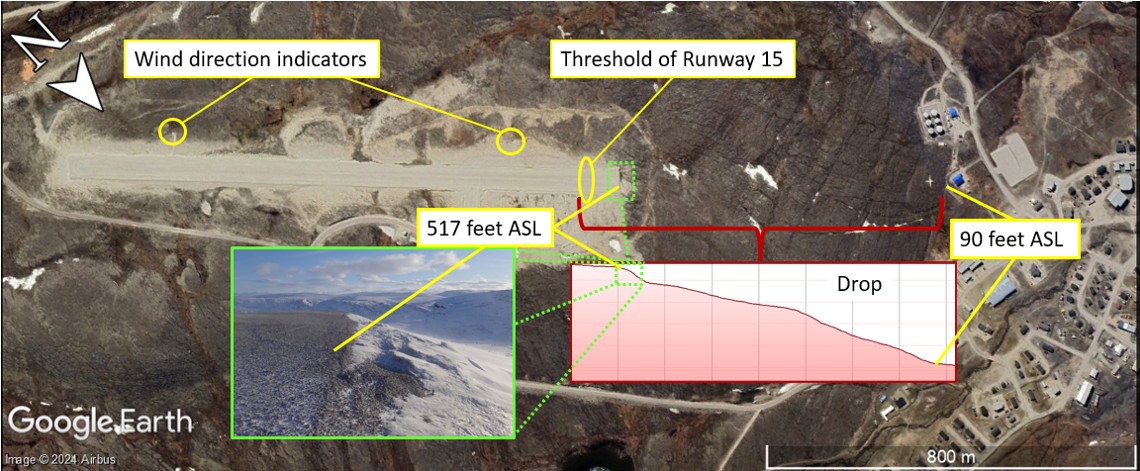

CYKG is approximately 1 km east-southeast of the municipality of Kangiqsujuaq. The airport and threshold for Runway 15 are at an elevation of 517 feet ASL. The airport is operated by the Kativik Regional Government. It has a single gravel runway, Runway 15/33, which is 3520 feet long and 100 feet wide. Runway 15 has a 1.7% downslope over the first 2132 feet, then 0.3% over the final 1388 feet.NAV CANADA, Canada Flight Supplement (effective 21 March 2024 to 16 May 2024), p. B514.

Runway 15/33 has the following lighting:

- Variable intensity white runway edge lights, installed along the entire length every 196.85 feetThese intervals correspond to 60 m as described in Transport Canada’s TP 312E, Aerodrome Standards and Recommended Practices, 5th edition (effective 15 January 2020).

- Threshold lights and runway end lights that appear red during takeoff and green during approach and landing

- Unidirectional flashing strobe runway identification lights at each end of the runway

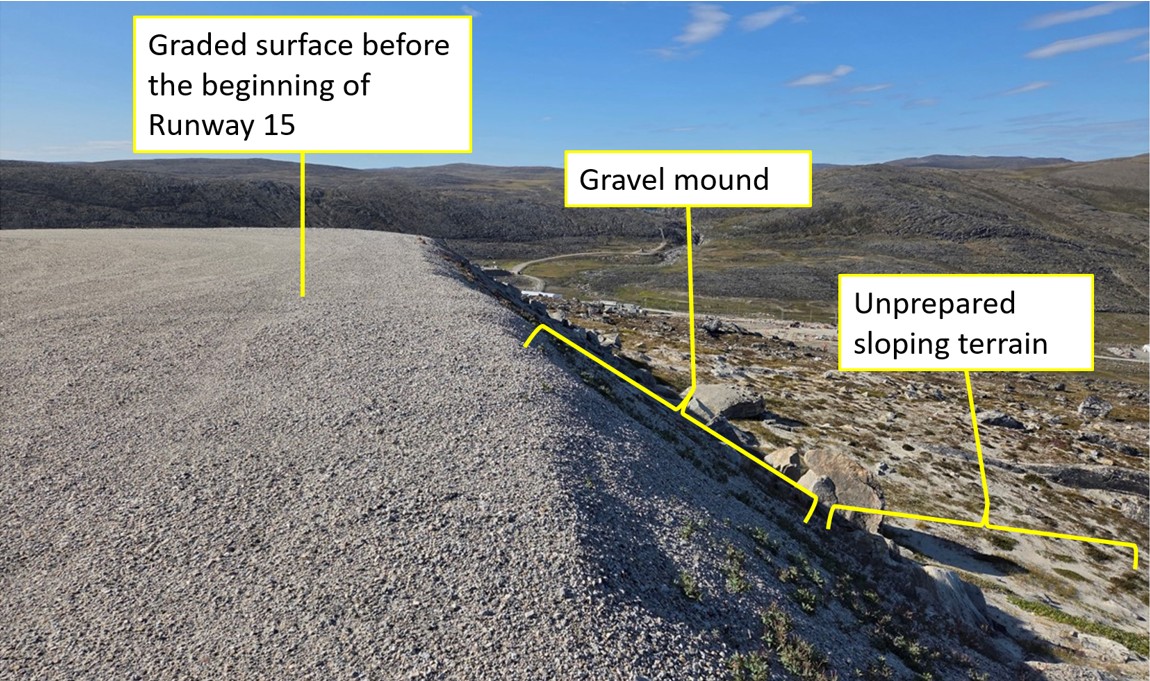

Wind indicators are located beside the runway, approximately 200 feet from the edge of the runway and approximately 500 feet beyond each runway threshold. The runway was built on top of a rocky hill, and the 220 feet leading up to the threshold of Runway 15 have been levelled with gravel to be at the same elevation as the runway (Figure 6). The thickness of the gravel creates a mound that reaches the unprepared terrain, which then drops to 90 feet ASL approximately 2600 feet from the threshold of Runway 15 (see Figure 2 in Section 1.1, History of the flight).

The topography around the airport means that when winds are greater than 20 knots, there is a risk of turbulence and wind shear. The Canada Flight Supplement warns pilots of this situation.NAV CANADA, Canada Flight Supplement (effective 21 March 2024 to 16 May 2024), p. B514.

1.11 Flight recorders

The aircraft was equipped with a flight data recorder (FDR) and a cockpit voice recorder (CVR). The 2 recorders were sent to the TSB Engineering Laboratory in Ottawa, Ontario, for download.

The FDR contained data for 133 flights, including the occurrence flight. An analysis of the data helped to establish the aircraft’s speed, path, pitch angle, vertical acceleration forces at touchdown, bank angles, flap position, propeller speed, engine power, terrain awareness and warning system alerts, and the PF’s use of the flight controls and the throttle.

According to the flight data, when the aircraft was in the final approach phase over the rising terrain, there was a negative vertical wind component. The maximum downward vertical wind was approximately 600 fpm about 0.25 NM from the runway threshold, 12 seconds before impact. The attitude then changed from 2.3° to 5.5° nose up. The purpose of this nose-up manoeuvre was to stop the descent so that the aircraft would not touch down before the beginning of the runway. During this manoeuvre, vertical wind effects were felt and the aircraft continued to descend.

The CVR, which contained high-quality audio recordings, had a rated recording time of 30 minutes, which complied with the Exemption from sections 605.34 and 605.34.3 of the Canadian Aviation Regulations (CARs)Transport Canada, NCR-014-2023, Exemption from sections 604.34 and 605.34.3 of the Canadian Aviation Regulations (signed and came into force 21 June 2023). at the time of the occurrence. The CVR provided an audio recording of the communications between the flight crew members before and during the occurrence.

1.12 Wreckage and impact information

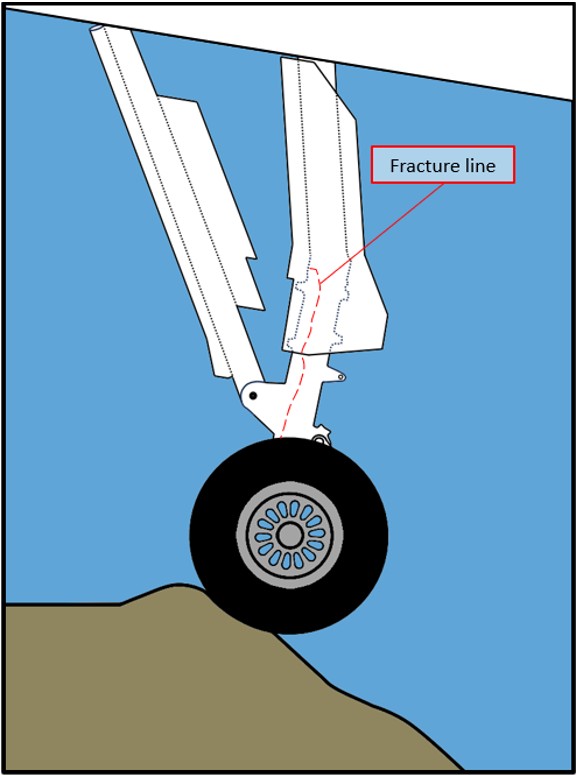

When the left landing gear struck the mound approximately 5 inches below the levelled part of the runway (Figure 7), the landing gear strut cylinder fractured (Figure 8), which led to the piston subassembly breaking off with the wheels attached.

During landing, the remaining part of the strut bent partially backward, and the propeller struck the surface of the runway. The aircraft came to a stop resting on the bent left landing gear and the other 2 intact landing gears. The left wing did not touch the ground (see Figure 3 in Section 1.1, History of the flight).

1.13 Medical and pathological information

There was no indication that the flight crew’s performance was negatively affected by medical or physiological factors, including fatigue.

1.14 Fire

There was no indication of fire either before or after the occurrence.

1.15 Survival aspects

Not applicable.

1.16 Tests and research

1.16.1 TSB laboratory reports

The TSB completed the following laboratory reports in support of this investigation:

- LP058/2024 – FDR [flight data recorder] Analysis

- LP059/2024 – CVR [cockpit voice recorder] Recovery and Analysis

- LP069/2024 – NVM [non-volatile memory] Data Recovery – FMS [flight management system]

- LP079/2024 – Fractography of Landing Gear

- LP093/2024 – Dash 8 Main Landing Gear Examination and Inventory

1.17 Organizational and management information

1.17.1 Air Inuit Ltd.

Air Inuit is a regional air carrier based out of Dorval that conducts scheduled and chartered flights to 22 destinations, mainly in Nunavik (Northern Quebec).

At the time of the occurrence, Air Inuit’s fleet consisted of 33 aircraft: 4 Boeing 737-200s, 1 Boeing 737-300, 3 Boeing 737-800s,The Boeing 737-800 aircraft were part of the fleet, but they were not yet in operation at the time of the occurrence. 3 Beechcraft 300s, 7 De Havilland DHC-6 Twin Otters, 12 De Havilland DHC-8-300s, and 3 De Havilland DHC-8-100s.

Air Inuit was operating the aircraft under subparts 702 (Aerial Work), 703 (Air Taxi Operations), 704 (Commuter Operations), and 705 (Airline Operations) of the CARs. The occurrence flight was conducted under Subpart 705.

Air Inuit monitors and manages operational risks using a safety management system (SMS) approved by Transport Canada. The system relies on instruments, such as a quality assurance program for flight operations and for the standard operating procedures, which have a feedback loop for identifying and mitigating safety risks.

1.17.1.1 Landing

After noting that its standard operating procedures recommended landing on the first third of the runway without actually designating an aiming point or recommended area for touchdown, Air Inuit modified the section on landings in January 2024 to include a best practiceA best practice is a type of guideline, advice, or principle, voluntary and non-binding, which describes an effective method without going into specific task-related details. for operations on runways without a visual glide slope indicator (VGSI). According to this best practice: “the aiming point on runway lengths of 3,937 feet (1200 m) and shorter should be the wind direction indicator when they are available at each end of the runway.”Air Inuit Ltd., Standard Operating Procedures Dash 8, Amendment 3 (01 January 2024), Section 2.7.2: Normal Landing, p. 226.

This best practice is based on information about aiming points published in the Transport Canada Aeronautical Information Manual (TC AIM).Transport Canada, TP 14371E, Transport Canada Aeronautical Information Manual (TC AIM), AGA - Aerodromes (21 March 2024), sections 5.4 and 5.9. All runways without VGSI in the Air Inuit airport network have wind direction indicators at each end of the runway, approximately 500 feet from each threshold, as is the case at CYKG.

1.18 Additional information

1.18.1 Landing distance calculations

The landing distances published in the aircraft flight manual were calculated based on the standards in Chapter 525 of the Airworthiness Manual (Transport Category Aeroplanes). Paragraph 525.125(a) has defined landing distance as:

The horizontal distance necessary to land and to come to a complete stop (or to a speed of approximately 3 knots for water landings) from a point 50 feet above the landing surface shall be determined (for standard temperatures, at each weight, altitude and wind within the operational limits established by the applicant for the aeroplane) […]Transport Canada, Airworthiness Manual, Chapter 525: Transport Category Aeroplanes, paragraph 525.125(a).

The landing distance published in the aircraft flight manual begins when the aircraft crosses the runway threshold at a height of 50 feet, continues for 840 to 1050 feet depending on the configuration of the aircraft (while the aircraft is still in the air), and ends with the ground roll.

According to the CARs dispatch limitations for landings at a destination aerodrome,

[…] no person shall dispatch or conduct a take-off in an aeroplane unless:

(a) the weight of the aeroplane on landing at the destination aerodrome will allow a full-stop landing […]

(ii) in the case of a propeller-driven aeroplane, within 70 per cent of the landing distance available (LDA);Transport Canada, SOR/96-433, Canadian Aviation Regulations, subsection 705.60(1).

To check whether this requirement is being met, it is necessary to calculate the factored landing distance, which corresponds to the dry landing distance published in the flight manual multiplied by 1.428. This factored distance is then compared to the stated usable runway length (i.e., the LDA).

In this occurrence, the (unfactored) landing distance for Runway 15 had been calculated to be 2220 feet,This distance includes a factor of 10% for a gravel runway and an average slope of −1.11% for Runway 15 at CYKG. which is the distance based on the certification conditions for the runway.

The factored distance adds a safety margin to ensure that the runway length will be long enough for the runway chosen. In this occurrence, the factored landing distance was 3170 feet,This distance was calculated using Air Inuit software, which includes the factor required by the Canadian Aviation Regulations, a factor of 10% for a gravel runway and an average slope of −1.11% for Runway 15 at CYKG. for a runway with an LDA of 3520 feet. The crew had access only to the factored distance in their flight planning documents.

For both factored and unfactored landing distances, a portion of the distance is covered while the aircraft is still airborne.

1.18.2 Aiming point

The aiming point is a designated spot on the runway where pilots fix their gaze during the final approach. It serves as a visual guide for pilots and helps them maintain an optimal glide path for landing.

The U.S. Federal Aviation Administration’s (FAA’s) Airplane Flying Handbook provides the following information on aiming points:

An airplane descending on final approach at a constant rate and airspeed travels in a straight line towards a spot on the ground ahead, commonly called the aiming point. If the airplane maintains a constant glide path without a round out for landing, it will strike the ground at the aiming point. […]

To the pilot, the aiming point appears to be stationary. It does not appear to move under the nose of the aircraft and does not appear to move forward away from the aircraft. […]

Note that the aiming point is not where the airplane actually touches down. Since the pilot reduces the rate of descent during the round out (flare), the actual touchdown occurs farther down the runway.Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), FAA-H-8083-3C, Airplane Flying Handbook, Chapter 9: Approaches and Landings, Section: Stabilized Approach Concept, p. 9-4 and 9-5, at https://www.faa.gov/sites/faa.gov/files/regulations_policies/handbooks_manuals/aviation/airplane_handbook/10_afh_ch9.pdf (last accessed on 09 December 2025).

Transport Canada’s Aerodrome Standards and Recommended Practices (TP 312) contains standards for visual aids used at aerodromes. TP 312 states that runways of 1200 m or less must have a wind direction indicator located centrally on the aerodrome or near each end of the runway. In the latter case, the wind direction indicator is typically positioned in proximity to the aiming point markings.Transport Canada, TP 312E, Aerodrome Standards and Recommended Practices: Land Aerodromes, 5th Edition, Amendment 1 (15 January 2020), Section 5.1.1.5, p. 87. This same information is also found in the TC AIM.Transport Canada, TP 14371E, Transport Canada Aeronautical Information Manual (TC AIM), AGA - Aerodromes (21 March 2024), Section 5.9.

According to information gathered during the investigation, on gravel runways less than 4000 feet long, it seems to be common practice for many pilots working at various air operators to use an aiming point that often corresponds to an area just beyond the runway threshold, or sometimes even a point before the runway threshold.

1.18.2.1 Decision regarding touchdown point

In July 2024, the Dutch Safety Board published an investigation report for an occurrence that was similar to this occurrence, involving an Airbus A330-300 that touched down 11 m before the runway threshold. This investigation report stated that the pilots were concerned by the runway length, particularly the narrow margin between the runway length and the landing distance necessary according to their calculations.

This perception that the runway was too short led the pilots to want to reduce the risk of an overrun by using a practice that is common for short runways. This practice consists in descending below the glide path to aim for a touchdown point at the beginning of the runway. However, at a height of approximately 60 feet, the aircraft was affected by wind gusts and a downdraft, which further modified the aircraft’s path and resulted in the aircraft touching down before the runway threshold.Dutch Safety Board, Touchdown before threshold: Risks associated with a large aircraft landing on a short runway (18 July 2024), at https://onderzoeksraad.nl/en/onderzoek/touchdown-before-threshold-airbus-a330-300-amsterdam-airport-schiphol/ (last accessed on 09 December 2025).

1.18.3 Touchdown zone

According to the Canada Air Pilot, a touchdown zone is “[t]he first 3000 feet of the runway or the first third of the runway, whichever is less.”NAV CANADA, Canada Air Pilot (CAP), CAP GEN: General Pages (effective 21 March 2024), p. 13. In the case of Runway 15 at CYKG, the touchdown zone extends from the threshold to 1173 feet (357 m).

1.18.4 Eye-to-wheel height

Transport Canada’s Advisory Circular 700-026 defines the eye-to-wheel height (EWH) as follows:

The highest expected vertical distance from the pilot’s eyes to the lowest portion of the aircraft at threshold crossing with maximum certificated landing weight in the normal landing configuration for the aircraft type and given glideslope.

Note: It is of importance to realize that this is not the physical dimension of the aircraft when at rest on the apron. It is the vertical distance in the landing configuration when the aircraft is rotated about the pitch angle and to the wheel path which follows the glideslope angle. The EWH is normally reported for a 3 degree glideslope, but may differ for other glideslopes.Transport Canada, Advisory Circular (AC) 700-026: Aircraft Eye Wheel Height Information (Issue No. 01: 7 August 2012), at https://tc.canada.ca/en/aviation/reference-centre/advisory-circulars/advisory-circular-ac-no-700-026 (last accessed on 09 December 2025). [bold and italics in original]

TSB Aviation Investigation Report A12Q0161, about an accident involving a DH8C that made a hard landing followed by an aft fuselage strike on the runway, explains that when the pilot’s eyes cross the runway threshold, the wheels have not yet reached the threshold, so the pilot has to take into account the horizontal and vertical distance that must be travelled by the wheels to reach the threshold. This vertical height between the pilot’s eyes and the wheel path (eye-to-wheel path height, or EWPH) is 11.9 feet for the DH8C at a pitch angle of 2°. This height varies depending on the aircraft’s pitch angle.

For the DH8C, the EWH and EWPH for various pitch angles are indicated in Table 3.

Pitch angle | Eye-to-wheel height (EWH) | Eye-to-wheel path height (EWPH) |

|---|---|---|

0° | 9.4 ft | 10.9 ft |

2° | 10.4 ft | 11.9 ft |

5.5° | 12.2 ft | 13.6 ft |

TSB Aviation Investigation Report A12Q0161 also indicated that in a normal landing configuration, on a descent angle of 3° with an aiming point at 300 feet from the runway threshold, the wheels of the DH8C will cross the runway threshold at a height of 3.8 feet.

Under the same conditions, if the aiming point is moved to the runway threshold, the wheels will touch down 228 feet before the threshold if the descent is not stopped.

1.18.5 Terrain and optical illusions

CYKG is located in an area that is characterized by rocky, uneven terrain. It has an upslope approach area (varying from 3.2% to 14.7% depending on the segment). This type of upsloping terrain in the approach area can create a visual illusion that influences the pilot’s perception of the aircraft’s descent path.

According to the Flight Safety Foundation’s report on the Runway Safety Initiative, an upslope in the approach area can create the illusion that the aircraft is too high. This illusion can cause the flight crew to correct its path by increasing the planned descent rate (e.g., a descent angle greater than 3°), or prevent the flight crew from recognizing when a descent angle is too low (e.g., a descent angle less than 3°).Flight Safety Foundation, Reducing the Risk of Runway Excursions: Report of the Runway Safety Initiative (May 2009), p. 105.

Finding: Other

In this occurrence, although the aircraft was flying below the glide path, the captain was aware of possible illusions at this location and visually maintained a constant descent angle of 3°.

2.0 Analysis

The investigation did not reveal any signs of an aircraft system, airframe, or engine failure that may have been a contributing factor in the occurrence flight. Furthermore, the aircraft’s performance was not considered to be a contributing factor. The flight crew held the appropriate licences and ratings for the flight, and there was no indication that the flight crew’s performance was degraded by fatigue or medical factors.

In this occurrence, the pilot flew as he normally would and brought the aircraft below the glide path to aim for a landing closer to the runway threshold. The analysis will therefore focus on this approach practice, including the descent below the glide path, the aiming point used, and the effects of the terrain and environmental conditions specific to Kangiqsujuaq (Wakeham Bay) Airport (CYKG).

2.1 Descent below the glide path and aiming point

During the visual portion of a final approach, pilots fix their gaze on a specific aiming point on the runway. When there are no aiming points or touchdown markings, pilots tend to aim for the threshold to touch down as soon as possible on gravel runways, which are susceptible to reduced braking effectiveness in the winter. This practice is meant to reduce the risk of a runway overrun. The investigation determined that this practice was widespread in operations on gravel runways shorter than 4000 feet.

Several factors could explain this practice, which is used to maximize the distance available for the ground roll during landing. The manufacturer’s landing performance calculations for this type of aircraft are based on an aircraft crossing the threshold at a height of 50 feet and touching down in the next 840 to 1050 feet. As a result, on a 3520-foot-long gravel runway like the one at CYKG, touchdown occurs in the last quarter of the touchdown zone. Pilots may have the impression that this distance between the threshold and touchdown is somehow lost for the ground roll, thereby reducing the safety margin for avoiding a runway overrun.

Air Inuit had published in its standard operating procedures a best practice based on Transport Canada’s TP 312 and the Transport Canada Aeronautical Information Manual (TC AIM). This practice recommended using the wind direction indicator as an aiming point for runways like the one at CYKG to allow for a touchdown from 500 feet beyond the runway threshold. As with the aircraft manufacturer’s calculations, pilots may have the impression that this distance is also lost for the ground roll, limiting the safety margin.

At Air Inuit, pilots had only the factored landing distances available in their flight planning documents. These distances, which are calculated during flight preparation and include a safety margin, are longer than the distance indicated in the aircraft flight manual. Furthermore, factored distances include the part of the distance when the aircraft is still airborne after crossing the runway threshold; this distance is unknown to the pilots. For this flight, the factored distance was calculated to be 3170 feet, which is only 350 feet less than the length of the runway (3520 feet). This information may have maintained the flight crew’s impression that they had only a small safety margin, especially with the changing runway conditions.

The TSB has previously identified the risks associated with a low approach that has an aiming point close to the runway threshold. In Aviation Investigation Report A12Q0161, the TSB indicated that if pilots descend below the optimum approach slope of 3°, there is an increased risk of collision with obstacles during approach and of landing short of the runway.

In this occurrence, the captain intended to perform a flare so that the aircraft would touch down after the runway threshold lights.

Finding as to causes and contributing factors

To minimize the risk of a runway overrun, the pilot was flying as he normally would for this type of operation, aiming to land near the runway threshold. He used an area just beyond the runway threshold as the aiming point and was visually following a descent angle of 3°. As a result, the aircraft was flying below the glide path on a trajectory where the wheels were going to touch down approximately 228 feet before the threshold if the descent was not stopped.

2.2 Effect of the terrain and environmental conditions on the approach

CYKG is located in an area with rocky, uneven terrain. The approach area is subject to downdrafts. At the end of the approach, the negative wind reading detected by the flight data recorder (FDR) confirms that the aircraft encountered a downdraft, which began pushing it toward the ground. The captain reacted by pitching the aircraft’s nose up and increasing power. When the aircraft was 5.5° nose up, the landing gear was approximately 12 feet lower than the pilot’s eyes. Even though this manoeuvre was successful in slowing down the inadvertent descent, it did not stop the descent and was not enough to prevent a touchdown before the start of the runway.

At CYKG, when the runway was built, the uneven terrain needed to be levelled at the top of the hill, creating a mound of gravel approximately 220 feet before the threshold. When the aircraft struck this mound, the left wheel touched the ground approximately 5 inches below the runway level, and the right wheel, approximately 4 inches below this level. This contact resulted in an overstress fracture in the left landing gear strut, and the strut detached from the wheel assembly.

Finding as to causes and contributing factors

Using an area just beyond the threshold as an aiming point placed the aircraft on a descent path leading to a touchdown before the runway threshold. The descent was not stopped owing to the effects of a downdraft. As a result, the touchdown occurred approximately 220 feet before the threshold, the wheels struck the mound below the runway level, and the left landing gear fractured.

3.0 Findings

3.1 Findings as to causes and contributing factors

These are the factors that were found to have caused or contributed to the occurrence.

- To minimize the risk of a runway overrun, the pilot was flying as he normally would for this type of operation, aiming to land near the runway threshold. He used an area just beyond the runway threshold as the aiming point and was visually following a descent angle of 3°. As a result, the aircraft was flying below the glide path on a trajectory where the wheels were going to touch down approximately 228 feet before the threshold if the descent was not stopped.

- Using an area just beyond the threshold as an aiming point placed the aircraft on a descent path leading to a touchdown before the runway threshold. The descent was not stopped owing to the effects of a downdraft. As a result, the touchdown occurred approximately 220 feet before the threshold, the wheels struck the mound below the runway level, and the left landing gear fractured.

3.2 Other findings

These findings resolve an issue of controversy, identify a mitigating circumstance, or acknowledge a noteworthy element of the occurrence.

- In this occurrence, although the aircraft was flying below the glide path, the captain was aware of possible illusions at this location and visually maintained a constant descent angle of 3°.

4.0 Safety action

4.1 Safety action taken

4.1.1 Air Inuit Ltd.

Following the occurrence, the Air Inuit Ltd. (Air Inuit) flight operations department carried out a detailed safety review of the findings and root causes identified in the investigation it conducted using its safety management system (SMS).

That investigation found that company pilots had a tendency to attempt to land close to the runway threshold on gravel runways. The investigation also found that flight crews did not always fully understand landing performance calculations. More specifically, they did not understand how much of a safety margin was already included in the calculations and that the calculations were based on crossing the threshold at a height of 50 feet.

Further to these findings, Air Inuit published an internal safety alert regarding the risks associated with short landings. This alert focused on the phase of flight when the runway is in sight and on the safe altitude margin when crossing the runway threshold. The flight plans for DH8C operations have been modified to include the aircraft flight manual unfactored landing distances for various flap positions in addition to factored landing distances.

Air Inuit then created a diagram depicting the touchdown zone for gravel runways, taking into consideration all of the types of aircraft used for its operations. This diagram was then incorporated into the company’s procedures and a training campaign was carried out with all of the company’s pilots.

The company’s stabilized landing criteria were updated, specifying that the vertical flight path is leading to the “desired touch down zone (DTDZ)”. Air Inuit defines the desired touch down zone as:

Other than Off Strip operations, the Desired Touch Down Zone is defined as an area between the first 500 feet of the runway and the first 1100 feet of the runway; [emphasis in original] or within the first third of the runway, whichever is less; measured from the threshold in the direction of landing [Figure 9].Air Inuit Ltd., Landing Performance & Landing Geometry (2024) [training document].

Air Inuit also made the following amendments to its training programs:

- detailed explanation of landing performance calculations based on various aiming points and approach angles;

- explanation of the eye-to-wheel height (EWH) and eye-to-wheel path height (EWPH) for DH8C aircraft, Boeing 737 aircraft, and Beechcraft 300 aircraft, depending on the pitch angle and approach angle;

- incorporation of the desired touchdown zone diagram in flight training and on the simulator for all aircraft operated by the company.

Air Inuit has not received any internal reports indicating that this procedure gives pilots the impression that they may not have enough runway length.

Air Inuit followed up on implementation of the procedure and all pilots were adhering to the practice, without any negative impacts on flight operations. This procedure does not appear to need any adjustments.

This report concludes the Transportation Safety Board of Canada’s investigation into this occurrence. The Board authorized the release of this report on 04 December 2025. It was officially released on 18 December 2025.

![Figure 4. Windflow in mountainous areas (Source: Environment Canada, AWARE: The atmosphere, the weather and flying [January 2011]) Figure 4. Windflow in mountainous areas (Source: Environment Canada, AWARE: The atmosphere, the weather and flying [January 2011])](/sites/default/files/2025-12/A24Q0027-figure-04-BIL.jpg)

![Figure 9. Diagram and definition of desired touch down zone (Source: Air Inuit Ltd. Landing Performance & Landing Geometry [training document]) Figure 9. Diagram and definition of desired touch down zone (Source: Air Inuit Ltd. Landing Performance & Landing Geometry [training document])](/sites/default/files/2025-12/A24Q0027-figure-09-BIL.jpg)