Controlled flight into terrain

Air Tindi Ltd.

De Havilland DHC-6 Twin Otter Series 300, C-GMAS

Diavik Aerodrome (CDK2), Northwest Territories, 7 NM SE

The Transportation Safety Board of Canada (TSB) investigated this occurrence for the purpose of advancing transportation safety. It is not the function of the Board to assign fault or determine civil or criminal liability. This report is not created for use in the context of legal, disciplinary or other proceedings. See Ownership and use of content. Masculine pronouns and position titles may be used to signify all genders to comply with the Canadian Transportation Accident Investigation and Safety Board Act (S.C. 1989, c. 3).

Summary

At 1205 Mountain Standard Time on 27 December 2023, the wheel-ski equipped Air Tindi Ltd. De Havilland Inc. DHC-6 Twin Otter Series 300 (registration C-GMAS, serial number 438) aircraft departed Margaret Lake, Northwest Territories, as flight TIN601, on a visual flight rules flight to Lac de Gras, Northwest Territories, with 2 flight crew members, and 8 passengers on board.

Upon arriving over the Lac de Gras road camp, the flight crew conducted 4 approaches toward the desired landing area on the frozen lake surface, descending at times to heights below 50 feet above ground level. During the 4th and final approach attempt, the aircraft descended to below 50 feet above ground level, and the flight crew lost visual contact with the terrain. At 1245 Mountain Standard Time, the aircraft impacted the terrain 1 nautical mile southeast from the desired landing site. Two passengers were seriously injured and were unable to egress. The remaining occupants, including one passenger who was ejected, sustained minor injuries. The aircraft was substantially damaged from the impact forces. There was no post impact fire. The emergency locator transmitter activated, and search and rescue personnel from the Canadian Armed Forces and a volunteer search party from Diavik mine, Northwest Territories, arrived on the scene 8 hours after the occurrence. The following morning, all but the volunteer search party were flown to Diavik Aerodrome (CDK2), Northwest Territories, and subsequently to Yellowknife Airport (CYZF), Northwest Territories.

1.0 Factual information

1.1 History of the flight

Cockpit voice recordings Annex 13 to the Convention on International Civil Aviation requires States conducting accident investigations to protect cockpit voice recordings.International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO), Annex 13 to the Convention on International Civil Aviation, Aircraft Accident and Incident Investigation, Thirteenth Edition (July 2024), paragraph 5.12. Canada complies with this requirement by making all on-board recordings—including those from cockpit voice recorders (CVR)—privileged in the Canadian Transportation Accident Investigation and Safety Board Act. While the TSB may make use of any on-board recording in the interests of transportation safety, it is not permitted to knowingly communicate any portion of an on-board recording that is unrelated to the causes or contributing factors of an accident or to the identification of safety deficiencies. The reason for protecting CVR material lies in the premise that these protections help ensure that pilots will continue to express themselves freely and that this essential material is available for the benefit of safety investigations. The TSB has always taken its obligations in this area very seriously and has vigorously restricted the use of CVR data in its reports. Unless the CVR material is required to both support a finding and identify a substantive safety deficiency, it will not be included in the TSB’s report. To validate the safety issues raised in this investigation, the TSB has made use of the available CVR information in its report. In each instance, the material has been carefully examined in order to ensure that it is required to advance transportation safety. |

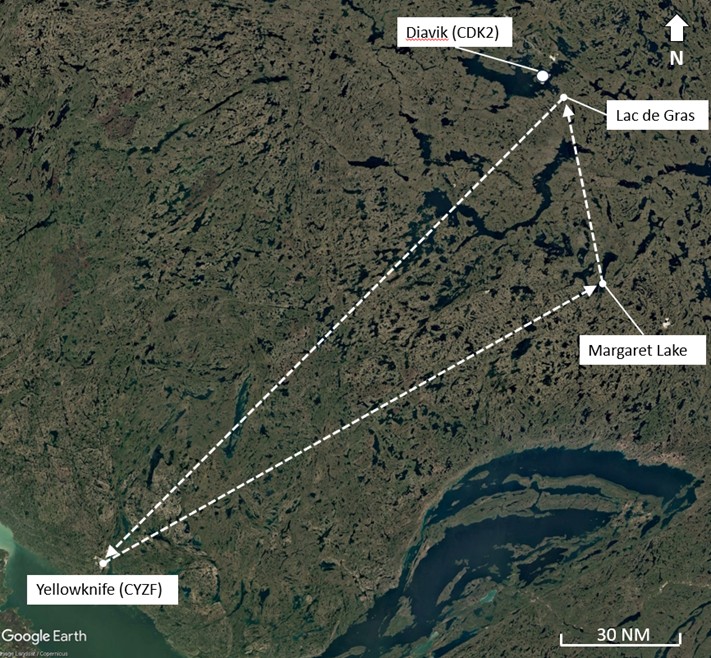

On 27 December 2023, two Air Tindi Ltd. (Air Tindi) De Havilland Inc. DHC-6 Twin Otter Series 300 (Twin Otter) aircraft were scheduled to depart Yellowknife Airport (CYZF)All locations mentioned in this report are in the Northwest Territories, unless otherwise noted. at 1000.All times are Mountain Standard Time (Coordinated Universal Time minus 7 hours). The Twin Otters were tasked with transporting workers and supplies to camps at Margaret Lake and Lac de Gras. After landing at Margaret Lake, one Twin Otter was to return to CYZF, and the occurrence aircraft, C-GMAS, would continue to land at Lac de Grasand then return to CYZF.

The occurrence aircraft was to conduct the 3 legs of its flight (as flight number TIN601) under visual flight rules (VFR)(Figure 1).

The first officer (FO) of the occurrence aircraft arrived at CYZF at approximately 0830 on the day of the occurrence and began checking the weather for the day. The FO then began to prepare the aircraft for departure.

Along with the captain, the FO reviewed the weather for the Gahcho Kué mine, Diavik Aerodrome (CDK2), and the surrounding area and proceeded to board 8 passengers for the flight to Margaret Lake. The captain would be the pilot flying (PF) for the first 2 legs, and the FO would be the pilot monitoring (PM).

At 1055, the flight crews of the 2 Air Tindi Twin Otters started their engines and prepared to depart from CYZF to Margaret Lake. Before departing, the flight crew of the occurrence aircraft briefed an initial en-route altitude of 1500 feet above ground level (AGL), with the plan to climb to a higher altitude later in the flight to take advantage of the strong westerly winds.

The occurrence aircraft departed CYZF at 1057, initially levelling off at a height of 1500 feet AGL. At 1104, in an effort to prevent unwanted terrain warnings announcing the hills near Lac de Gras, the flight crew disabled the aircraft’s terrain awareness and warning system (TAWS) by pulling the circuit breaker.

Shortly after the system was disabled, the occurrence aircraft began a climb through a layer of ice crystals, which it exited at 1109. It then proceeded to fly over the layer of ice crystals at an altitude of approximately 5500 feet above sea level (ASL).

At 1138, the occurrence aircraft began its descent to Margaret Lake. The flight crew observed the other Twin Otter’s approach and landing at Margaret Lake through the automatic dependent surveillance – broadcast (ADS-B) input on their electronic flight bags (EFBs).Electronic flight bags (EFBs) are explained in detail in Section 1.17.10 Electronic flight bag of this report.,The investigation was unable to determine which EFB was used when, only that they were used. This is reflected in the language used in the report.

At approximately 15 nautical miles (NM) from the improvised airstrip,An improvised airstrip is an unimproved surface used by an aircraft to land and take off as opposed to a runway, which is an improved, established, and monitored surface for aircraft to land and take off. the occurrence aircraft was levelled off at 500 feet AGL, and then it continued inbound toward the airstrip. At a distance of 1 NM from the airstrip, the flight crew spotted the camp that was adjacent to the surface where the flight crew was planning to land. The occurrence aircraft joined a left-hand downwind, remaining within ½ NM of the improvised airstrip, and completed the turn to final. At a distance of 0.2 NM from the airstrip, the aircraft lined up on final with aid from the airstrip markers. The aircraft touched down at 1152.

While on the ground, the occurrence aircraft flight crew discussed the fact that the weather was deteriorating, as well as options for conducting visual approaches in reduced visibilities on their next leg to Lac de Gras should the weather continue to deteriorate.

At 1158, the flight crews in both aircraft started their engines with the intention of backtracking down the airstrip together and then departing one after the other. The occurrence aircraft backtracked first, followed by the 2nd Twin Otter. Having reached the end of the airstrip, the occurrence aircraft flight crew turned into the wind and could not see the other Twin Otter, which was still backtracking, because of the blowing snow. The 2nd Twin Otter flight crew could not see the occurrence aircraft either and therefore opted to conduct a maximum performance short takeoff from halfway down the airstrip. The flight crew of the occurrence aircraft was able to confirm that the 2nd Twin Otter had departed once it could see it had climbed above the blowing snow and was turning toward CYZF.

At 1205, the occurrence aircraft flight crew commenced their take-off run from the improvised airstrip and initially levelled off at approximately 500 feet AGL for the flight to Lac de Gras.

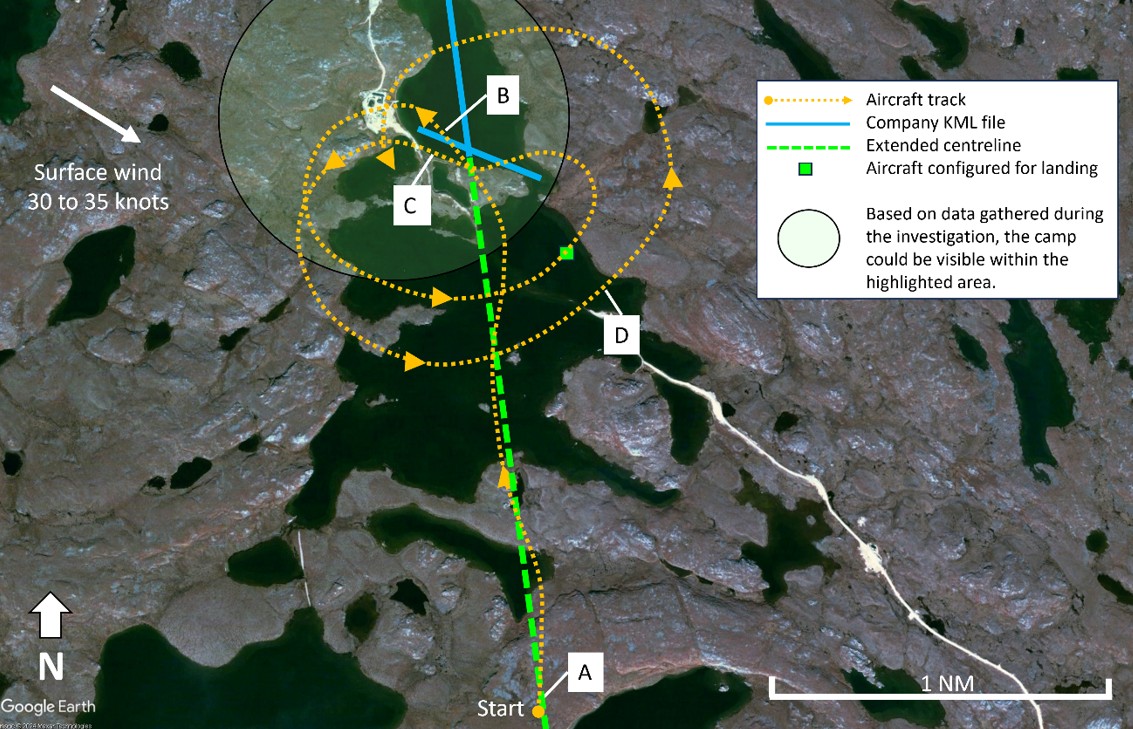

While en route, the aircraft remained below the ceiling, which the flight crew estimated to have decreased to between 300 and 400 feet AGL with approximately ½ statute miles (SM) of forward visibility in light freezing drizzle. The flight crew considered the possibility of doing an improvised instrument approachImprovised instrument approaches are discussed in more detail in Section 1.17.7.4 Improvised approach procedures of the report. to Lac de Gras. At 1222, the flight crew attempted to contact the CDK2 universal communications station (UNICOM) for the station-reported weather. They waited a few minutes and called a 2nd time. Shortly after, they received a weather report indicating that winds were from 300° magnetic (M) at 25 knots gusting to 32 knots, with ½ SM visibility in blowing snow. The flight crew then loaded the Air Tindi Keyhole Markup Language (KML) fileKeyhole Markup Language (KML) is a format used to display geographical information through moving map applications such as Google Earth or ForeFlight. KML files are discussed in more detail in Section 1.17.6.1.1 Company Keyhole Markup Language files of the report. for the Lac de Gras road camp airstrip, which was on the lake’s frozen surface, into their respective EFBs. The PM extended the centreline for the north-south landing surface from the file on his EFB to provide lateral guidance into the Lac de Gras road camp airstrip from a greater distance away. The PF then intercepted the approach course 2.5 NM from the intended landing surface with guidance from the PM, who was using the EFB (A on Figure 2).

At 1228, at a distance of 1¾ NM from the Lac de Gras road camp and a height of 220 feet AGL, flaps to 10° were selected to help slow the aircraft. The flight crew spotted the road camp 1 minute later when they were at a distance of ½ NM. The aircraft overflew the road camp at 250 feet AGL and began a left-hand circuit for a visual inspection of the intended landing surface (B on Figure 2). While on the base leg for the inspection, the flight crew put the aircraft in a landing configuration,The landing configuration of flaps 20° and propellers levers full forward may also be used for inspection passes. (setting the flaps to 20° and the propellers levers full forward) (green square on Figure 2). After turning final, while overflying the desired landing surface at a height of between 50 and 100 feet AGL for the inspection pass, the flight crew was unable to differentiate the shoreline from the ice on the lake on which they intended to land and conducted a go-around (C on Figure 2).

The occurrence aircraft began a left-hand orbitFor the purposes of this report, an orbit is a circular path with no intention to land, as opposed to a circuit, which is a similar circular path, but with an attempt to land. of the desired landing area (D on Figure 2). While orbiting the landing area, the flight crew determined that the visibility and ceiling would not allow for a visual approach (Table 1).

Event | Time (hhmm:ss) | Height (feet AGL) | Ground speed (knots) | Event description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

A | 1228:07 | 215 | 92 | Intercepted approach course |

B | 1229:25 | 250 | 70 | Overflew the road camp |

C | 1230:56 | 50 | 55 | Conducted a go-around |

D | 1231:59 | 495 | 123 | Left-hand orbit of the desired landing surface |

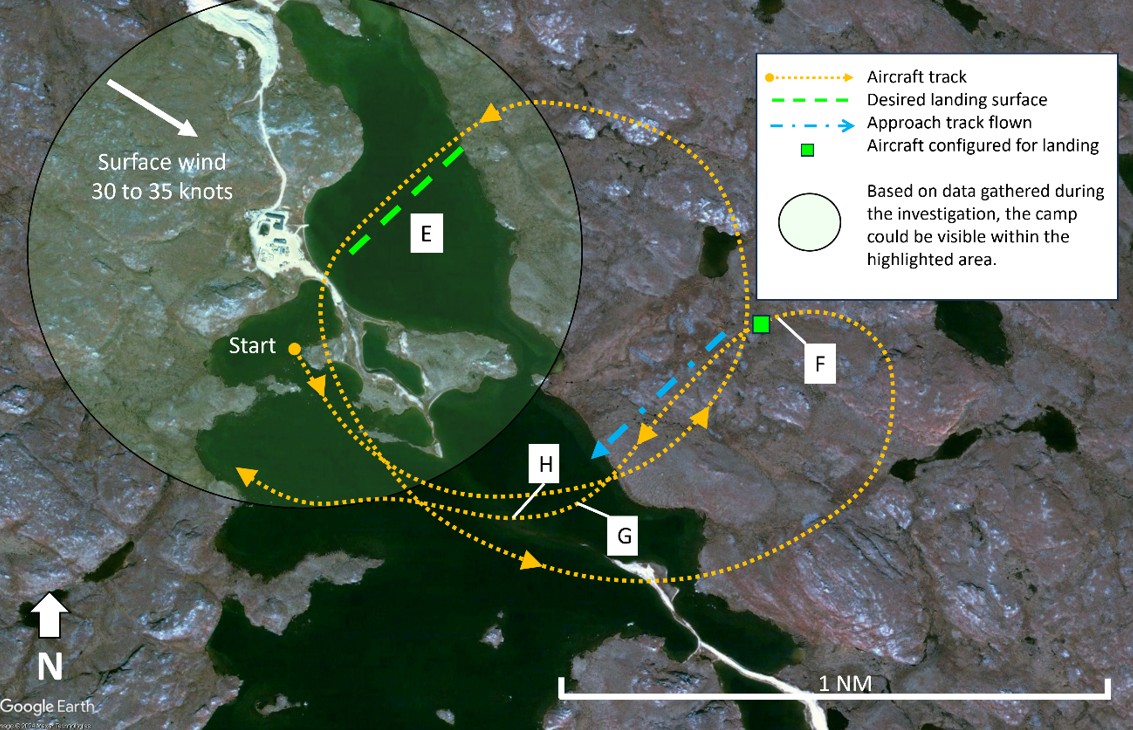

The occurrence aircraft conducted a 2nd orbit of the desired landing area to determine an appropriate heading for an improvised omni-bearing selector (OBS) approach.Section 1.17.7.4.2 Omni-bearing selector approach/heading approach of the report contains more information on this improvised instrument approach procedure. The flight crew agreed it would be best to conduct an improvised OBS approach to a new desired landing surface on a heading of 220°M (E on Figure 3). Approximately 1 NM to the east of the new desired landing surface, at an altitude of 290 feet AGL, a left turn was initiated, and the aircraft rolled out on an approach heading of 220°M (F on Figure 3) at approximately 155 feet AGL without compensating for the strong westerly winds. Once the turn was complete, the aircraft was aligned ½ NM to the southeast of the desired landing surface. The aircraft was configured for landing (green square on Figure 3) and continued the improvised instrument approach to between 100 and 50 feet AGL. With the aid of his EFB, the PM determined the aircraft was not aligned with the desired landing surface, and a go-around was initiated (G on Figure 3). During the go-around, at approximately 120 feet AGL, the flight crew entered instrument meteorological conditions (IMC)IMC or instrument meteorological conditions means meteorological conditions less than the minima specified in Part VI, Subpart 2, Division VI of Transport Canada’s Canadian Aviation Regulations (CARs) for visual meteorological conditions, expressed in terms of visibility and distance from cloud. and were unable to determine their position visually (H on Figure 3) (Table 2).

Event | Time (hhmm:ss) | Height (feet AGL) | Ground speed (knots) | Event description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

E | 1234:32 | 245 | 76 | Determined new desired landing surface and approach heading |

F | 1235:53 | 155 | 75 | Rolled out on heading 220°M |

G | 1236:12 | 50 | 57 | Initiated a go-around |

H | 1236:20 | 120 | 54 | Entered IMC |

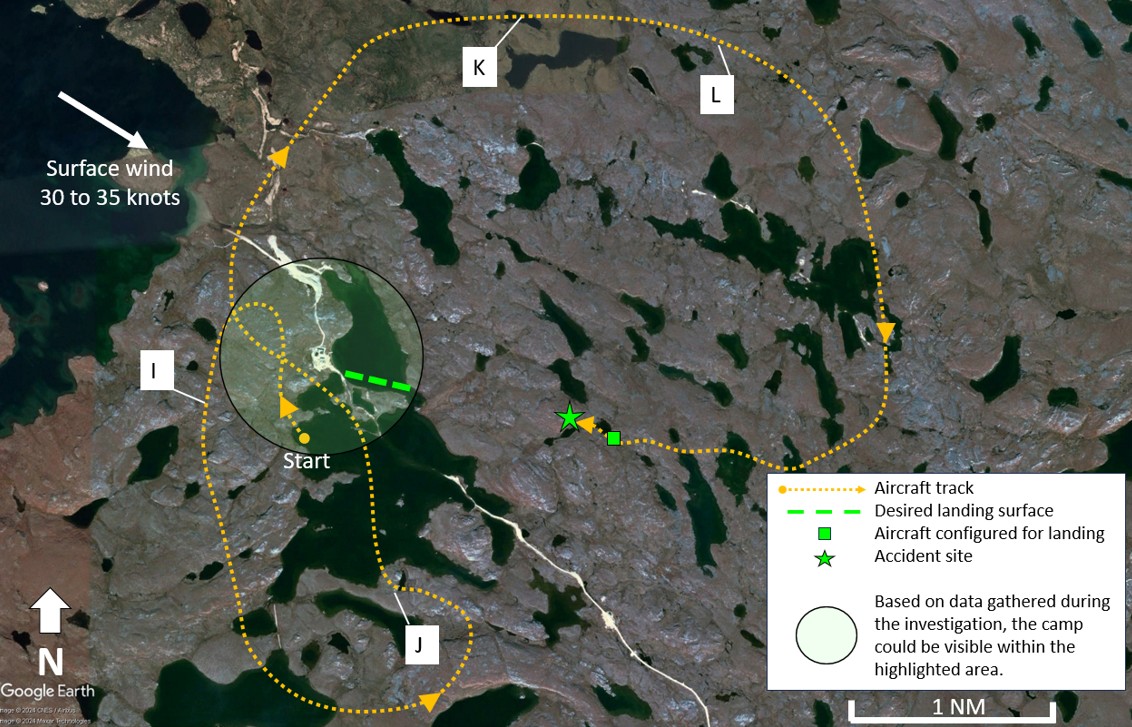

While the aircraft climbed back up to approximately 300 feet AGL, the flight crew began to program a new improvised extended centreline approach into the EFB. The aircraft commenced a left-hand circuit (I on Figure 4) for a 3rd approach to a northbound landing. During the turn from downwind to final, the aircraft overshot the desired northbound track but then intercepted it with the flight crew’s use of an approach built on the EFB (J on Figure 4). Unable to see the lake, the flight crew relied on the EFB for positional information. Once the flight crew spotted the road camp approximately ½ NM away, they determined that the crosswind was too high to continue with a northbound landing, and the aircraft again entered a go-around of the road camp.

After the go-around, the aircraft began to drift upwards, steadily gaining altitude, and entered a right-hand downwind 2 NM to the north of the road camp (K on Figure 4). At 1241, the PF indicated on an EFB that he intended to fly a modified right-hand circuit and approach the road camp on a westerly heading, and the PM proceeded to build a 4th improvised approach into the EFB. On the downwind leg, the aircraft inadvertently climbed to approximately 1000 feet AGL (L on Figure 4). At the time of the 4th approach, the visibility was approximately ½ SM. During the base leg, the aircraft began descending (Table 3).

Event | Time (hhmm:ss) | Height (feet AGL) | Ground speed (knots) | Event description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

I | 1237:43 | 280 | 96 | Left-hand circuit for northbound approach |

J | 1239:40 | 155 | 62 | Intercepted desired northbound approach track |

K | 1242:01 | 700 | 124 | Right-hand downwind for westbound approach |

L | 1242:41 | 1000 | 130 | Inadvertent climb to 1000 feet AGL |

When the aircraft rolled out on final, it was approximately 2 NM from the road camp and at 150 feet AGL. After establishing the aircraft on the final approach course, the flight crew relied on the EFB guidance to determine their position relative to the desired landing path. The aircraft continued to descend to approximately 50 feet AGL on the final approach course. The PM was verbally providing lateral guidance to the PF based on the track on his EFB. At 1245:20, the aircraft was configured for landing (green square on Figure 4). When the aircraft was 1.5 NM from the desired landing surface, the PF descended below 50 feet AGL in anticipation of landing. At 1245:28, both flight crew members saw a hill in the windscreen. The PF applied full power, and both pilots pulled aft on the yoke to initiate a pitch up. The last recorded ground speed of the aircraft was 44 knots. The aircraft impacted the terrain 2 seconds later at 1245:30.

The aircraft came to rest balanced on the crest of the hill, with half of the aircraft overhanging the edge. The emergency mode on the aircraft SKYTRAC ISAT-200A tracking system was activated by the FO at 1247:50, notifying Air Tindi of the accident. The Canadian Mission Control Centre (CMCC) in Trenton, Ontario, received an emergency locator transmitter (ELT) signal from the aircraft on the 406 MHz frequency at 1248.

The Diavik mine assembled a volunteer search party to assist with the rescue. The search party departed from the mine at 1904 on 4 snowmobiles with additional winter survival equipment, travelling to the site at night through a blizzard. Canadian Armed Forces search and rescue technicians (SAR Techs) and the Diavik mine volunteers arrived at the scene at approximately the same time, at 2036.The search and rescue operation is discussed in more detail in Section 1.15 Survival aspects of the report.

Everyone stayed at the occurrence site overnight. The next morning, everyone but the Diavik mine volunteer search party was airlifted to CDK2 and subsequently flown to CYZF. The search party from Diavik mine rode their snowmobiles back to the mine.

1.2 Injuries to persons

There were 2 flight crew members and 8 passengers on board.

Table 4 outlines the degree of injuries received.

Degree of injury | Crew | Passengers | Persons not on board the aircraft | Total by injury |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Fatal | 0 | 0 | – | 0 |

Serious | 0 | 2 | – | 2 |

Minor | 2 | 6 | – | 8 |

Total injured | 2 | 8 | – | 10 |

1.3 Damage to aircraft

The aircraft was substantially damaged by impact forces.See Section 1.12 Wreckage and impact information of the report for more details.

1.4 Other damage

There was no other damage.

1.5 Personnel information

Captain | First officer | |

|---|---|---|

Pilot licence | Airline transport pilot licence (ATPL) - Aeroplane | Commercial pilot licence (CPL) - Aeroplane |

Medical expiry date | 01 May 2024 | 01 December 2024 |

Total flying hours | approximately 14 300 | approximately 400 |

Flight hours on type | approximately 8000 | approximately 200 |

Flight hours in the 24 hours before the occurrence | 1.8 | 1.8 |

Flight hours in the 7 days before the occurrence | 3.6 | 16.6 |

Flight hours in the 30 days before the occurrence | 14.1 | 64.6 |

Flight hours in the 90 days before the occurrence | 66.3 | 167.1 |

Flight hours on type in the 90 days before the occurrence | 66.3 | 167.1 |

Hours on duty before the occurrence | 2.8 | 4.2 |

Hours off duty before the work period | 110 | 66 |

The captain was the PF during the occurrence flight and was sitting in the left seat. The FO was the PM and occupied the right seat.

1.5.1 Captain

The captain was hired by Air Tindi in 2008 as a captain on Beechcraft King Air aircraft, a position that he held for approximately 2.5 years. On 05 June 2010, he completed his line indoctrination as a captain on Twin Otter aircraft. On 12 July 2011, approximately 1 year after completing his line indoctrination, he was made a training captain on the Twin Otter. At the time of the occurrence, the captain flew both the Twin Otter and Single Otter aircraft as an off-strip captain,Off-strip or off-airport flying is a term used to describe the takeoff and landing of aircraft where no runway has been constructed. It may include operations on wheels, floats, or skis. Off-strip captain is a term used by Air Tindi to describe the pilot-in-command of an aircraft operating off-strip. operating aircraft on wheels, skis, and floats. Before joining Air Tindi, the captain had worked for a different Canadian air operator in Ontario, flying Cessna Caravan, Pilatus PC-12, and Twin Otter aircraft in airport-to-airport and off-strip operations.

The captain’s most recent Twin Otter pilot proficiency check was completed on 30 October 2023.

The captain held the appropriate licence and ratings for the flight in accordance with existing regulations.

1.5.2 First officer

The FO joined Air Tindi in 2021 as a flight dispatcher. During his time as a dispatcher, he worked toward his commercial pilot licence. He obtained his commercial pilot licence on 15 March 2023. On 20 April 2023, he successfully completed a Twin Otter pilot proficiency check and was promoted to part-time FO on the Twin Otter beginning on 01 August 2023. The FO was then promoted to a full-time flying position on 17 November 2023. This is a typical progression for new pilots at Air Tindi.

The FO held the appropriate licence and ratings for the flight in accordance with existing regulations.

1.6 Aircraft information

1.6.1 General

The occurrence aircraft, a De Havilland Inc. DHC-6 Twin Otter Series 300, is a twin-engine turboprop aircraft that features a high wing with struts, fixed landing gear, and an unpressurized cabin. The aircraft was designed as a rugged short takeoff and landing commuter, capable of off-airport takeoffs and landings. To achieve the short takeoff and landing performance, the Twin Otter was designed to have a low stall speed allowing it to conduct approaches at low speeds. The aircraft is certified for single-pilot operations, but many air operators often operate the aircraft with a flight crew of 2, as in the occurrence flight. At the time of the occurrence, the occurrence aircraft was equipped with wheel skis and seating for 9 passengers.

Manufacturer | De Havilland Inc.* |

|---|---|

Type, model, and registration | DHC-6 Twin Otter Series 300, C-GMAS |

Year of manufacture | 1974 |

Serial number | 438 |

Certificate of airworthiness | 09 April 1976 |

Total airframe time | 51 995.2 hours |

Engine type (number of engines) | Pratt & Whitney Canada PT6A-27 (2) |

Propeller type (number of propellers) | Hartzell HC-B3TN-3DY (2) |

Maximum allowable take-off weight | 12 500 lb (5669 kg) |

Recommended fuel types | Jet A, Jet A-1, Jet B |

Fuel type used | Jet A-1 |

* De Havilland Aircraft of Canada Limited is the current type certificate holder for the DHC-6.

There were no recorded defects outstanding at the time of the occurrence. There was no indication that a component or system malfunction played a role in this occurrence.

The aircraft’s weight and centre of gravity were within the prescribed limits.

1.6.2 Flight instruments

1.6.2.1 Terrain awareness and warning system

The occurrence aircraft was equipped with a Sandel ST3400 TAWS/RMI (radio magnetic indicator) unit, which is a TAWS Class A and Class B system. This met the requirements of the Canadian Aviation Regulations (CARs).Transport Canada, SOR/96-433, Canadian Aviation Regulations (CARs), subsection 703.71(1). The CARs also stipulate that the aircraft may be operated without being equipped with an operative TAWS if the aircraft is operated in day VFR only or if it is necessary, in the interest of aviation safety, for the pilot-in-command to deactivate it.Ibid., subsection 703.71(2).

The unit is capable of providing flight crews with various levels of alerts ranging in urgency from amber caution alerts to red warning alerts. Amber caution alerts require a pilot’s immediate attention whereas red warning alerts require immediate aggressive pilot action.Sandel, ST3400 TAWS/RMI with Traffic Capability: Pilot’s Guide (February 2004), Responding to an Alert, p. 47. When an aircraft is operating from aerodromes with runways under 2500 feet in length or from improvised strips, of which neither are in the unit’s database, the unit provides a TAWS INH (inhibit) function that cancels all forward-looking terrain avoidance and premature descent alerts but does not cancel basic ground proximity warning system alerts. The aircraft flight manual does not provide a specific procedure for a response to a TAWS warning; however, the Air Tindi Flight Operations Manual (FOM) provides guidance as to the actions to be taken in the event of a ground proximity warning.Air Tindi Ltd., Flight Operations Manual, Edition 4: Version 7 (09 December 2022), section 13.36: TAWS/EGPWS Procedures, p. 13-44.

Given the distraction caused by having both cautions and warnings activated during off-strip landings, Twin Otter pilots at Air Tindi would disable the TAWS by pulling the circuit breaker. Following discussions with 11 Air Tindi pilots, the investigation determined that there was no common procedure on when to disable the TAWS. The company does not provide any guidance on whether or when the TAWS should be disabled.

1.6.2.2 Radio altimeter

Radio altimeters detect the height of the aircraft above ground in real time and are effective up to 2500 feet AGL. They have no ability to look forward – they can only detect height immediately below the aircraft. The occurrence aircraft’s radio altimeter was functional at the time of the occurrence.

Air Tindi provides guidance for pilots in VFR flight in the form of a common procedure in the FOM, that states the following:

Unless specific airframe configurations preclude it, both pilots shall have Radio Altitude and related alerting information set upon commencing descent from cruise altitude (carried out as part of the descent checklist). Where possible, both pilots Radio Altimeter Alert Heights should be set to the same value.Ibid., section 13.35.2: Common Procedures, p. 13-43.

There is a company-wide standard practice to have the radio altimeter set to 500 feet AGL while operating in VFR conditions. Because of the high workload during off-strip operations, pilots would often disable the radio altimeter warnings by setting the selector to either the highest or lowest setting, to avoid the distraction of the warning while on final approach. The investigation determined that there was no specific moment for pilots to disable the warning, but it was common to disable the warnings either once the pilots could see the desired landing area or at the top of descent while in visual meteorological conditions (VMC).

During the accident, the radio altimeter was set to 200 feet AGL.

1.7 Meteorological information

1.7.1 Reported weather

1.7.1.1 Station-reported weather at Diavik Aerodrome

A privately operated weather reporting station at Diavik Aerodrome (CDK2) issued weather reports at 1100, 1200, and 1300 (occurrence time 1245). The information contained in those reports is included in Table 7.

Conditions | At 1100 | At 1200 | At 1300 |

|---|---|---|---|

Winds | 270°T/15 kt | 290°T/22 to 27 kt | 300°T/30 to 35 kt |

Visibility (statute miles) | 10 SM | 3 SM in blowing snow | ¼ SM in blowing snow |

Ceiling (feet above ground level) | Overcast at 900 ft AGL | Overcast at 500 ft AGL | Overcast at 1000 ft AGL |

Temperature/Dew point (degrees Celsius) | −3 °C/−3 °C | −4 °C/−4 °C | −6 °C/−6 °C |

Altimeter setting (inches of mercury) | 29.14 inHg | 29.18 inHg | 29.22 inHg |

At 1223, approximately 10 NM from the Lac de Grasroad camp, the flight crew received the following weather report from CDK2 over the radio:

- Winds from 300° true (T) at 25 knots, gusting to 32 knots

- Visibility of ½ SM in blowing snow

- Altimeter setting of 29.20 inHg

1.7.1.2 Aerodrome forecast for Yellowknife Airport

An aerodrome routine meteorological report (METAR) was issued at 0440 on the day of the occurrence for Yellowknife Airport (CYZF) containing the information in Table 8.

Time | Wind (degrees true/knots) | Visibility (statute miles) | Clouds (feet above ground level) |

|---|---|---|---|

From 0700 | 230°T/15 to 25 kt | More than 6 SM | Scattered clouds at 1500 and 18 000 ft AGL |

Temporary between 0700 and 1300 | N/A | N/A | Broken ceiling at 1500 ft AGL and additional broken layer at 18 000 ft AGL |

From 1300 | 280°T/18 to 28 kt | More than 6 SM | Few clouds at 1500 ft AGL |

Becoming at 1800 | 280°T/10 to 20 kt | More than 6 SM | N/A |

1.7.1.3 Graphic area forecast

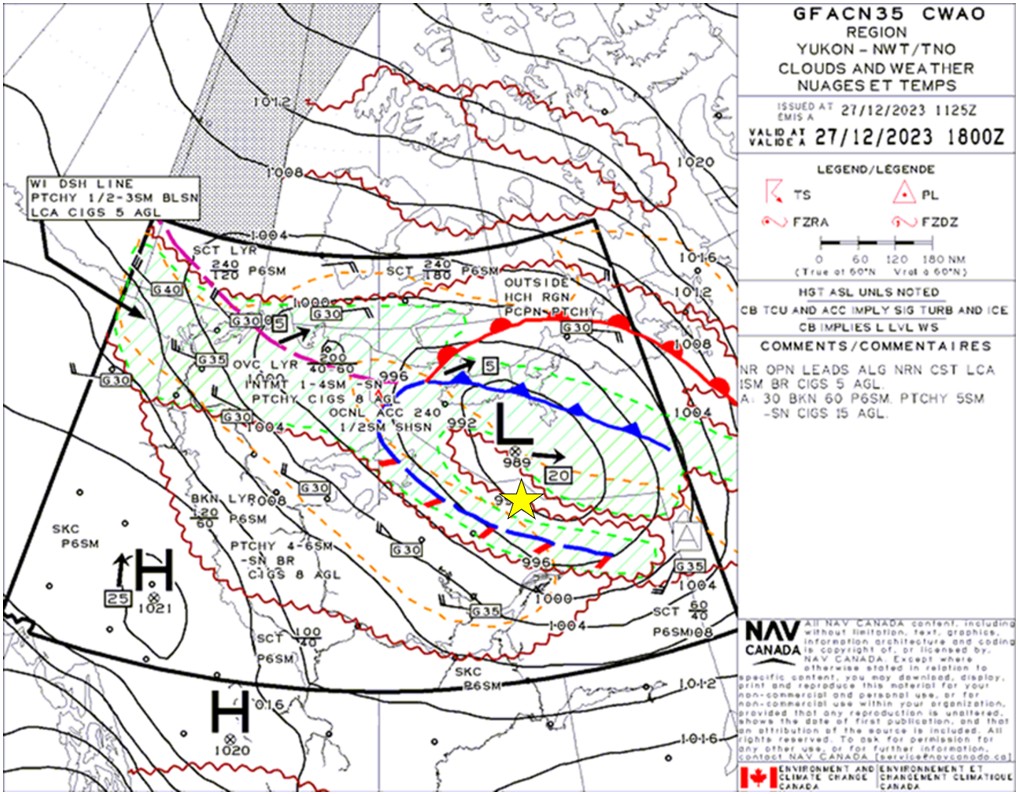

Very little meteorological information is available for the area of the occurrence. The only predictive meteorological information produced by NAV CANADA for this area is the graphic area forecast (GFA). According to the GFA that was available to the flight crew before departure and valid during the occurrence flight,Graphic area forecast issued by NAV CANADA at 0425 on 27 December 2023, and valid from 1100 to 2300 on 27 December 2023. the flight would be operating in an area of localized ceilings based at 500 feet AGL and patchy visibility of ½ SM to 3 SM in blowing snow (Appendix A).

1.8 Aids to navigation

The aircraft was equipped with 2 Garmin GNS 430W GPS (global positioning systems) with a limited moving-map showing large bodies of water, terrain outlines, and real-time aircraft position. The aircraft was also equipped with a Garmin Flight Stream 210, which allows position information from the Garmin GNS 430W to be broadcast to the flight crew’s EFBs and the ForeFlight Mobile application (ForeFlight).

ForeFlight allows real-time aircraft position information to be overlaid on aeronautical maps, such as VFR navigation charts.

1.9 Communications

The occurrence aircraft was equipped with a SKYTRAC ISAT-200A, which is a GPS and an Iridium transceiver that provides voice, text messaging, flight following, and data communications with global coverage. The unit provides automatic position reporting, with a default reporting interval of 1 minute that begins at either the “Transceiver On” or “Engines On” event, depending on how the aircraft is wired.

Aircraft position information (location, altitude, track, speed, time up, and time down) can be viewed on SKYTRAC’s web application SkyWeb in real time. At the time of the occurrence, Air Tindi used the SKYTRAC system as part of its flight watch.

The SKYTRAC ISAT-200A has 2 modes of operation: NORM [normal] and EMERG [emergency], selected by a two-way locking toggle on the unit’s face. In the NORM mode, it sends position reports according to the reporting interval and can also be used as a satellite phone to provide two-way voice communication through a pilot’s headset to any other phone. In the EMERG mode, the unit can automatically increase the frequency of position reports, send an email or text message notification to designated recipients, and change the colour of the aircraft icon in the SkyWeb application to bright red while giving visual and aural alerts.

The Air Tindi FOM states that if an emergency occurs, pilots are to activate the emergency mode (EMERG) by actioning the toggle switch.Air Tindi Ltd., Flight Operations Manual, Edition 4: Version 7 (09 December 2022), section 8.7: Flight Following and Communications, p. 8-5.

1.10 Aerodrome information

Not applicable.

1.11 Flight recorders

The aircraft was not equipped with a flight data recorder, nor was it required by regulation.

However, the aircraft was equipped with an automatic dependent surveillance-broadcast system, which provided the investigation with significant information about the flight path of the aircraft, including the altitude, the track, and the ground speed.

The aircraft was also equipped with a CVR that had a recording capacity of 120 minutes. The CVR data was successfully downloaded at the TSB Engineering Laboratory in Ottawa, Ontario; it included both flights on the date of the occurrence and contained good quality audio.

1.12 Wreckage and impact information

The wreckage was located on the crest of a snow-covered hill in a nose-high attitude (Figure 5), with the rear half of the aircraft overhanging the edge (Figure 6). There was considerable damage to the underside of the fuselage; both main landing gears collapsed and the nose gear compressed into the fuselage. The right-hand engine separated at the power turbine, with the hub and propeller left loosely attached.

1.13 Medical and pathological information

There was no indication that the performance of the flight crew members was negatively affected by medical or physiological factors, including fatigue.

1.14 Fire

There was no indication of fire either before or after the occurrence.

1.15 Survival aspects

1.15.1 General

After the aircraft came to rest, the flight crew assessed both the passengers and themselves for injuries; most had injured backs, and the FO had a sprained ankle.

The FO initially switched the SKYTRAC ISAT-200A to the EMERG mode to report the accident and the aircraft’s current position to Air Tindi dispatch and then switched the unit back to the NORM mode to use the satellite phone. The FO attempted to call Air Tindi but was unable to make contact because the headsets of both flight crew members were broken. He then switched the unit back to the EMERG mode.

The captain exited the aircraft through the left-hand (PF’s) door and observed that several passengers had already exited the aircraft, including the passenger who had been seated adjacent to the rear cargo door on the rearmost seat. This passenger was ejected from the aircraft through the rear cargo door when their seat became dislodged during the impact sequence. The captain assisted the FO out of the aircraft through the PF door. The captain and 2 passengers then began to secure the aircraft’s nosewheel ski to a rock with ratchet straps to provide extra stability and prevent the aircraft from sliding backwards down the hill. The remaining passengers began assembling a 6-person tent to provide shelter and provided first aid to both the FO and the more injured passengers.

Despite the low visibility and quickly approaching nighttime, several passengers started to walk in the direction of the Lac de Gras road camp (located 1.25 NM to the west); however, they were encouraged to return to the aircraft by the captain, and all passengers and flight crew remained at the aircraft to wait for rescue.

Two passengers, unable to egress owing to their injuries, remained in the aircraft and were joined by the captain, who remained with them until the SAR Techs arrived and extricated them. In an effort to preserve heat, the aircraft’s engine tents were used to block the doors of the aircraft and as makeshift blankets.

One passenger produced, from his luggage, a satellite phone that the captain used to contact Air Tindi to report the accident and the occupants’ conditions and to coordinate the rescue.

At 1250, the CMCC relayed the ELT signal it had received to the Joint Rescue Coordination Centre (JRCC) in Trenton, which dispatched a Hercules aircraft with SAR Techs from Winnipeg, Manitoba, at 1306.

The JRCC had also contacted 2 local helicopter operators (at 1330) and the Canadian Armed Forces’ 440 Squadron in Yellowknife (at 1332) to determine whether they could provide immediate assistance. Both helicopter operators were limited to day VFR operations and 440 Squadron was limited to day VFR operations for off-strip landings. Sunset at the accident site was at 1421, and given the distance from Yellowknife, none of these operators would be able to arrive at the site during daylight.

The Diavik mine had assembled a volunteer search party to assist with the rescue. The volunteers departed from the mine at 1904 on 4 snowmobiles with additional winter survival equipment and began the 6 NM trip, travelling to the site at night through a blizzard.

The Hercules aircraft arrived overhead of the site at 1900; however, owing to the weather conditions upon arrival, the pilots of the Hercules only spotted the occurrence aircraft at 1949. The SAR Techs successfully parachuted to the occurrence aircraft at 2036. At roughly the same time, the volunteer search party arrived on snowmobiles. By 2352, the SAR Techs had extricated the 2 remaining passengers from the aircraft and provided medical assistance.

Heated shelters were erected below the hill, and all people at the site spent the night in the shelters. Everyone but the volunteer search party was retrieved the following morning via helicopter and flown to CDK2, where Air Tindi aircraft were waiting. The seriously injured passengers were flown back to CYZF on a MEDEVAC-equipped Beechcraft King Air aircraft and subsequently taken to hospital. The rest of the occurrence aircraft occupants returned to CYZF on an Air Tindi De Havilland Inc. DHC-7 aircraft. The Diavik mine volunteer search party returned to the mine using the snowmobiles.

1.15.2 Safety harness

All the passengers and the flight crew were wearing their lap belts at the time of the accident. Although the FO was wearing his lap belt, he was not wearing the shoulder harness of the 5-point restraint system. The CARs specify that for landings, pilots must be seated with their safety belts fastened, including the shoulder harness.Transport Canada, SOR/96-433, Canadian Aviation Regulations (CARs), subsection 605.27(a).

1.15.3 Emergency locator transmitter

The aircraft was equipped with a Kannad 406 AF ELT unit that sent a 406 MHz signal to the SARSAT satellites.

1.15.4 Survival kit

Subsection 602.61(1) of the CARs specifies that

[…] no person shall operate an aircraft over land unless there is carried on board survival equipment, sufficient for the survival on the ground of each person on board, given the geographical area, the season of the year and anticipated seasonal climatic variations, that provides the means for

(a) starting a fire;

(b) providing shelter;

(c) providing or purifying water; and

(d) visually signalling distress.Ibid., subsection 602.61(1).

The occurrence aircraft was equipped with a survival kit that the company had interpreted to meet the requirements of CARs subsection 602.61(1). During the occurrence, the survival kit was difficult to access by the flight crew as it was stored in the aft baggage compartment, which was overhanging the edge of the hill after the impact.

The standard survival kit carried on board the aircraft and used during the occurrence was contained in a hard plastic case. The kit included food capable of providing 5000 Kcal per person for 12 people and the following equipment:

- 12 foil blankets;

- 6 four-hour candles;

- 2 mess tins;

- 2 nine-foot-long pieces of heavy aluminum foil;

- 12 foil containers;

- 12 insect headnets;

- 2 insect repellants;

- 2 knives with sheaths;

- 4 light sticks;

- 4 tubes of waterproof matches;

- 2 tubes of windproof matches;

- 1 heliograph mirror;

- 1 fifty-foot-long parachute cord;

- 1 pocket saw;

- 2 nine-feet by twelve feet tarps for shelter;

- 1 fire starter;

- 2 tinder;

- 1 strobe light and batteries;

- 1 survival manual;

- 4 spoons;

- 1 sewing kit;

- 2 eight-m-long pieces of flagging tape;

- 1 package of 30 water purification tablets;

- 2 pealess whistles; and

- 2 coreless rolls of toilet tissue.Label describing the survival kit (Model FE 12A) that was on board the occurrence aircraft.

A tent was added to the survival kit on board the occurrence aircraft; however, the tent that was carried on the aircraft was not large enough for the number of people on board, which forced them to lay on top of each other to fit inside and shelter from the environment.

Air Tindi has a more robust survival kit, which includes tents and sleeping bags as well as the standard kit content, for pilots to equip the aircraft with if they deem it warranted. These kits are typically only carried on longer (multiday) flights away from the base. Generally, the standard survival kit is carried on flights that return to Yellowknife on the same day.

1.16 Tests and research

1.16.1 TSB laboratory reports

The TSB completed the following laboratory report in support of this investigation:

- LP049/2024 – CVR Audio Recovery

1.17 Organizational and management information

1.17.1 General

Air Tindi was founded in 1988 and has operated out of CYZF since its inception. Air Tindi is authorized to operate under the following CARs subparts: 702 (Aerial Work), 703 (Air Taxi Operations), 704 (Commuter Operations), and 705 (Airline Operations).

The company operates a fleet of 17 single- and multi-engine turboprop aircraft and provides daily scheduled flights servicing isolated communities, air ambulance services, and charter flights for mining, tourism, government, and community support services throughout northern Canada.

At the time of the occurrence, Air Tindi operated 6 Twin Otter aircraft. It was certified to operate Twin Otter aircraft under subparts 702, 703, and 704 of the CARs in day and night VFR and instrument flight rules (IFR) flights. The occurrence flight was being operated under Subpart 703 (Air Taxi Operations) of the CARs.

1.17.2 Organizational structure at Air Tindi Ltd.

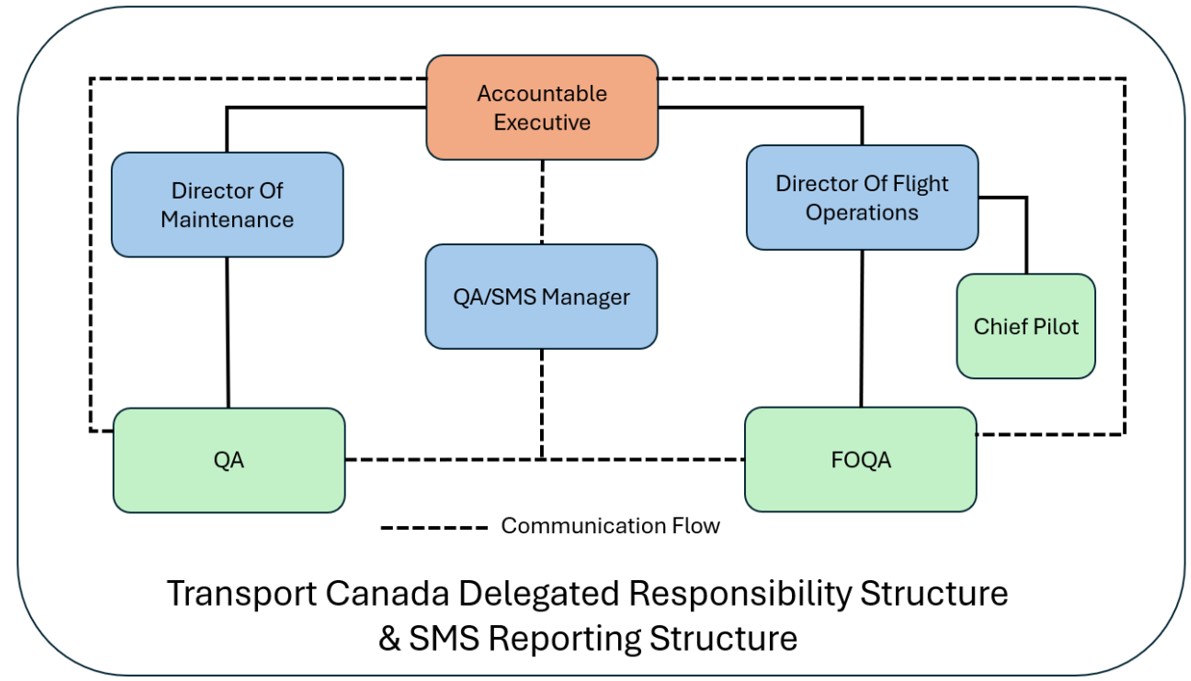

At the time of the accident, Air Tindi’s organizational structure was as shown in Figure 7.

According to the FOM, at Air Tindi,

[t]he Accountable Executive is responsible for establishing and maintaining the overall corporate culture, for providing the functional heads with the necessary resources to comply with the regulations and maintain the necessary levels of safety, and is accountable for the functionality and development of the Safety Management System.Air Tindi Ltd., Flight Operations Manual, Edition 4: Version 7 (09 December 2022), section 6.5.1, p. 6-4.

The manual goes on to describe the director of flight operations’ main responsibility, which is to ensure flight operations are safe. This includes, without being limited to:

- control of operations and operational standards of all aeroplanes operated; […]

- supervision, organization, function and manning of the following:

- flight operations;

- cabin safety; […]

- training programs; […]

- safety management system; […]

- assurance that company operations are conducted in accordance with current regulations, standards and company policy;Ibid., section 6.5.2, p. 6-5.

At Air Tindi, the person who takes on the role of chief pilot becomes responsible for the establishment and implementation of professional standards to guide the flight crews under their authority. This includes, without being limited to:

- developing standard operating procedures;

- developing and/or implementing all required approved training programs for the flight crew; […]

- supervising of flight crew;Ibid., section 6.5.3, p. 6-6.

1.17.3 Operational control system

Air Tindi uses a Type C pilot self-dispatch operational control system for its CARs subparts 702, 703, and 704 operations. Under a Type C pilot self-dispatch system, the director of flight operations is responsible for the operational control system and delegates operational control of flights to the captains, while retaining the responsibility for the day-to-day conduct of flight operations.

1.17.4 Managerial oversight of line pilots

Compliance with operational policies and procedures at Air Tindi is primarily conducted through the training program, pilot proficiency checks, line checks,Flight crew members’ qualification requirements found in CARs 703.88 do not include a line check nor are line checks required to be conducted by a delegate of the Minister (i.e., an approved check pilot). Line check flight test reports are not submitted to Transport Canada. and a hazard registry that helps identify safety hazards in the organization. The system of oversight also relies on pilots reporting issues through the company safety management system (SMS).

Operational issues are often dealt with less formally rather than through the SMS, with pilots discussing issues with their superiors (assistant chief pilots, chief pilot) and the issues being dealt with through informal meetings and by word of mouth.The investigation conducted several interviews with pilots and a summary is discussed in more detail in Section 1.17.13 Information gathered from Air Tindi Ltd. Pilots of the report.

Air Tindi also uses a flight operations quality assurance (FOQA) program to aid in providing oversight on flights. At the time of the occurrence, there was an FOQA coordinator, who reported to the SMS manager. The FOQA coordinator position largely entailed assisting in preparing the company for audits (client, regulator, and internal) and occasionally aiding the SMS manager with investigations if required.

1.17.4.1 Flight data monitoring

In typical IFR operations, flight paths and parameters are mostly predictable; therefore, the use of flight data monitoring (FDM) is a good tool to catch deviations. However, FDM becomes more complicated when dealing with operations outside typical airport-to-airport flights. During off-strip operations, aircraft are frequently required to circle the intended landing area numerous times to confirm safety-critical parameters (wind speed and direction, obstacles on the landing surface, taxi routes, or the required performance for takeoff and landing). Further to this, by the nature of VFR flying, aircraft may be required to change heading and altitude frequently during a typical flight. At the time of the occurrence, the FOQA program did not utilize FDM nor was it required by regulation.

1.17.5 Flight operations manual

The Air Tindi FOM (version 7 of the 4th Edition) was approved by Transport Canada (TC) on 23 December 2022. The purpose of the manual is to provide “management and operations personnel with instructions and guidance for the conduct of a safe and efficient air service.”Air Tindi Ltd., Flight Operations Manual, Edition 4: Version 7 (09 December 2022), section 1.2: Preamble, p. 1-2. The manual also states that “[t]he company requires that personnel know the contents of the manual and apply the policies and procedures accordingly.”Ibid., section 1.2: Preamble, p. 1-2.

With regards to this occurrence, the following sections of the FOM that outline specific responsibilities for various individuals are relevant.

For the captain:

The Captain is responsible to the Chief Pilot for the safe conduct of assigned flights. Specific duties include: […]

checking weather, all applicable NOTAMs where available, determining fuel and oil requirements; […]

conducting flights in strict adherence with the company aeroplane Standard Operating Procedures (when applicable); and,

conducting flights in accordance with Canadian Aviation Regulations, the Aircraft Flight Manual, and this Flight Operations Manual.Ibid., section 6.6.10: Captain, p. 6-15.

For the FO:

The First Officer’s duties include, but are not limited to the following: […]

- conduct flights in strict adherence with the company aeroplane Standard Operating Procedures; [emphasis in original]

- conduct flights in accordance with Canadian Aviation Regulations, the Aircraft Flight Manual, and this Flight Operations Manual; […]

- assist the Captain in the management and operation of the flight;

- participate in the execution of cockpit procedures, emergency procedures, checklist procedures, and instrument approach procedures as directed by the Captain and, in accordance with the procedures outlined in this manual, the Aircraft Flight Manual, [emphasis in original] and the aircraft Standard Operating Procedures; [emphasis in original] […]

- shall be responsible to inform the Captain immediately of any situation when the aircraft is being handled improperly or placed in jeopardy.Ibid., section 6.6.11: First Officer, pp. 6-15 and 6-16.

The section that outlines VFR flight requirements also contains relevant information. With regards to day VFR operations below 1000 feet AGL, the FOM states that flight visibility must not be less than 2 miles, and the aircraft must be operated clear of cloud. This is consistent with the CARs minimum weather for VFR flight below 1000 feet AGL.Transport Canada, SOR/96-433, Canadian Aviation Regulations (CARs), section 602.115. Air Tindi pilots are forbidden to continue VFR flights when they are incapable of maintaining an altitude of more than 500 feet AGL and a flight visibility of at least 2 miles.Air Tindi Ltd., Flight Operations Manual, Edition 4: Version 7 (09 December 2022), section 10.2.2: VFR Flight Requirements, p. 10-4. The FOM also states that pilots should not attempt to continue flying VFR when encountering IMC.Ibid., section 10.4.2: Controlled Flight into Terrain (CFIT) Avoidance Procedures, p. 10-11.

1.17.6 Visual meteorological conditions operations at Air Tindi Ltd.

1.17.6.1 Company Keyhole Markup Language files

KML is a file format used to display information in a geographic context through many applications such as Google Earth or ForeFlight. Information in a KML file can be added as a layer to an existing map or scene. In doing so, a KML file can provide a reference line for pilots to follow.

At Air Tindi, KML files are uploaded to the EFBs via a document cloud application, which then allows the files to be imported into ForeFlight. The company-created KML files are intended to be used as guidance during VFR approaches to locations without certified approach procedures, allowing pilots to line up on final with off-strip locations from a greater distance than if only visual navigation was used. The KML files also allow for better situational awareness while circling in relatively featureless terrain, providing a PM with a constant visible track on their EFB. The KML file for the Lac de Gras road camp displayed 2 landing areas on the lake, one in a northwest to southeast direction and one in an east-west direction.

The only formal guidance provided by Air Tindi for pilots was in the form of an online EFB training course that states the following:

3.9 USING KML (Keyhole Markup Language) FILES

This feature is commonly used for company procedures to locations that do not typically have approaches such as Tundra and Mould Bay. It allows for the importing and displaying of custom maps shapes into ForeFlight.

For additional information on its use and function, the following video is provided:

ForeFlight Feature Focus: Use Map Shapes: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RXUEIOWSJrA&feature=youtu.beAerostudies Inc., Ascent aviation e-training system, EFB Training 2024, section 3.9 Using KML Files, p. 32.

1.17.7 Instrument meteorological conditions operations at Air Tindi Ltd.

When the weather is below the prescribed VFR limits and it is not possible to maintain visual contact with the terrain, aircraft are to be operated under IFR. On a standard precision instrument approach, aircraft are able to safely operate down to an altitude that is 200 feet AGL with a forward visibility of ½ statute mile. To fly in IMC, aircraft are to be equipped with the required flight instruments.Transport Canada, SOR/96-433, Canadian Aviation Regulations (CARs), section 605.18. The occurrence aircraft was equipped and certified for IFR flight. In addition, to fly in IMC, pilots are required to hold an instrument rating. The occurrence flight crew members both held the required rating.

1.17.7.1 Minimum instrument flight rules altitudes

During flight in IMC, aircraft are required to maintain a certain altitude for given phases of flight to ensure terrain separation.Ibid., section 602.124. Minimum IFR altitudes are the lowest altitudes established for use in a specific airspace that provide a guaranteed terrain separation. It may be a minimum obstacle clearance altitude, a minimum en-route altitude, a minimum safe altitude, a safe altitude within a radius from a point in space, or a missed approach altitude. In the absence of a published minimum IFR altitude and given the geographic location of the occurrence, an aircraft operated under IFR is required to maintain a minimum altitude of 1000 feet above the highest obstacle located within a horizontal distance of 5 NM from the estimated flight path.Ibid., paragraph 602.124(2)(a).

1.17.7.2 Instrument approach procedures

Instrument approach procedures provide pilots with set procedures to transition from instrument flight to a visual landing. These procedures provide guaranteed terrain separation provided that the procedures are followed within the tolerances of their design.Transport Canada, TP308E, Criteria for the Development of Instrument Procedures, Change 9.0 (01 January 2024). Although there are instrument approaches at CDK2, there are no published instrument approach procedures for the road camp at Lac de Gras.

1.17.7.3 Let-down procedures

A common procedure for transitioning from IMC to VMC at remote locations that are not serviced by published instrument approach procedures is to conduct a controlled descent to a predetermined minimum IFR altitude. This altitude is often derived from IFR sector heights, nearby airport minimum safe altitudes, or maps that show terrain. During normal operations, descent below a minimum IFR altitude must only be conducted if visual reference has been established at or above a minimum IFR altitude.

Air Tindi’s FOM states the following:

When transition[sic] from IFR to VFR at airports without a current instrument approach, or airports without current weather, the following procedures must be briefed (prior to descent) and flown:

Minimum altitude authorized when descending in IMC conditions to an airport without a published instrument approach is the lower of:

- 2000' above the highest obstacle within 10 nautical miles of a destination GPS fix; or

- The MOCA [minimum obstacle clearance altitude], AMA [area minimum altitude] as published on LE charts [en route low altitude charts], or MSA [minimum safe altitude] (if near an airport with an approach) based on a local altimeter setting.Air Tindi Ltd., Flight Operations Manual, Edition 4: Version 7, (09 December 2022), section 10.7.1: Let-down Procedure, p. 10-24.

1.17.7.4 Improvised instrument approach procedures

For the purpose of this report, improvised instrument approach procedures is considered to be all procedures developed without certification for the purpose of operating an aircraft in IMC below a published IFR safe altitude. These procedures have become adaptations to established IFR procedures. Unlike certified approaches, improvised approaches have not gone through a certification process and thus do not guarantee terrain or obstacle clearance provided by the guidance in TC’s Criteria for the Development of Instrument Procedures.Transport Canada, TP308E, Criteria for the Development of Instrument Procedures, Change 9.0 (01 January 2024).

1.17.7.4.1 Radio altimeter improvised instrument approach procedure

A practice adopted by Air Tindi pilots at the time of the occurrence was to set the radio altimeter to aid with conducting an improvised instrument approach to a lower altitude than a minimum IFR altitude. The common practice at Air Tindi was to set 500 feet on the radio altimeter as an acceptable descent altitude for regions in the tundra, where terrain height does not vary drastically, and man-made structures do not exceed that height. Pilots would fly in IMC down to the height above ground level set in the radio altimeter in a manner similar to a minimum descent altitude on published non-precision approaches. Several Air Tindi pilots also expressed that setting the descent altitude below 500 feet on the radio altimeter was also a common practice if they felt that terrain was not a factor.

1.17.7.4.2 Omni-bearing selector approach/heading approach

A method to get lateral guidance to conduct an improvised instrument approach is using the OBS or by following a fixed heading. On many GPS units, it is possible to set an OBS track to any waypoint in the database or any user-created waypoint. Once an OBS track is selected, the aircraft’s horizontal situation indicator can provide lateral guidance to or from a waypoint on a specified desired track. This is often used in conjunction with the radio altimeter to provide both lateral and vertical guidance.

When an OBS track is not used in conjunction with the aircraft’s horizontal situation indicator, and only a heading is flown, wind drift will not be detectable. Although the aircraft may be facing the desired direction, the track over the ground may not be as intended as the aircraft will drift with the wind. The investigation was unable to determine if the flight crew referred to the OBS during the improvised instrument approaches conducted during the occurrence flight.

1.17.7.4.3 Improvised area navigation approaches

Improvised instrument approaches may also be constructed through the on-board global navigation satellite system devices, such as the Garmin GNS430, or with the EFB, through the use of “user waypoints”. Like the KML files, these can provide point-to-point lateral guidance and can also be programmed to show a pseudo-glideslope for vertical guidance.

1.17.8 Standard operating procedures

The Air Tindi standard operating procedures (SOPs) for the Twin Otter were reviewed and accepted by TC on 26 February 2020. The SOPs are issued for “guidance in the operation of the Twin Otter aircraft within the limitations of the Aircraft Flight Manual.”Air Tindi Ltd., De Havilland Twin Otter (DHC-6) Standard Operating Procedures, Edition 1, Version 2 (01 February 2020), chapter 1, section 1.2: Preamble, p. 1-2. The SOPs state the following:

Although SOPs ensure standardization for flight crewmembers to complete their duties, they do not encompass all situations. Crewmembers are therefore expected to exercise judgment and consistency in their application. Any deviations from the SOPs should be thoroughly briefed and understood by all concerned.Ibid.

The SOPs refer to the FOM for direction on how the various procedures are to be performed.

1.17.9 Approach briefings

The information required to be briefed varies for a VFR approach and an IFR approach. VFR approaches require a briefing of the landing runway and approach speeds as well as a threat review.As outlined in Air Tindi Ltd.’s Flight Operations Manual, Edition 4: Version 7 (09 December 2022), section 13.29.3: Threat Based Briefings, p. 13-35, during a threat review, the pilot monitoring is required to name any relevant threats for the procedure being briefed as well as strategies to mitigate them. The pilot flying must then signal any further perceived threats and mitigation strategies. If no threats exist, the flight crews are not required to brief threats. For an IFR approach, the flight crew is required to brief the type of approach, the landing runway, the primary navigation source, the minimum descent altitude, the approach speeds, the missed approach procedure, and the missed approach altitude. The flight crew is also required to conduct a threat review.Air Tindi Ltd., Flight Operations Manual, Edition 4: Version 7 (09 December 2022), section 13.29.3: Threat Based Briefings, p. 13-34.

Flight crew approach briefings at Air Tindi are presented in the FOM, which states the following:

Prior to each take-off or landing, crews will conduct a threat based briefing. The primary objective of these briefings includes: […]

PM lists any relevant threats for briefed procedure, with strategies to mitigate the threat(s)

PF follows up with any further perceived threats, with strategies to mitigate

If no perceived threats exist, crews are not required to brief any threats

Crew may reference type specific threat management cards, located onboard each aircraft.Ibid.

During the occurrence flight, the flight crew did not conduct any formal approach briefing or associated threat review. They did, however, periodically throughout the flight, identify the poor weather, icing conditions, and the aircraft’s gross operating weight. They also discussed that the 4th approach attempt would be their last before returning to CYZF.

1.17.10 Electronic flight bag

1.17.10.1 General

Air Tindi equips its pilots with EFBs to assist in various aspects of flight preparation and execution. These devices are loaded with applications that replace traditional paper-based materials. The EFBs provide easy access to the company’s FOM, SOPs, and other essential documents, ensuring that pilots have the latest information at their disposal.

In accordance with Air Tindi’s FOM, both the captain and the FO had an EFB in the form of an iPad mini.Ibid., section 13.19: Electronic Flight Bag (EFB) Operations, p. 13-18. These devices were equipped with ForeFlight, which includes maps, charts, weather information, manuals, and checklists required for planning and carrying out a flight. This application, in conjunction with the Garmin Flight Stream 210 device installed in the aircraft, provided GPS navigation functions in the form of own-ship display on the device. ForeFlight is also capable of providing synthetic visionThe synthetic vision displays an artificially generated view of the terrain outside the aircraft. to both pilots on their respective EFBs, if selected. Selection of this view is made by tapping the appropriate icon in a toolbar at the top of the display. This toolbar is visible at all times when using the application.

The document cloud application, which acts as a document repository linked to a server, allowing for easy synchronization of documents for every EFB at the company, was also installed on the EFBs. The company would keep documents such as airstrip condition reports specific to destinations not published in NAV CANADA’s Canada Flight Supplement in discrete folders for easy access by pilots. The document cloud application is also capable of storing KML files in these folders.

1.17.10.2 Electronic flight bag usage at Air Tindi Ltd.

Pilots undergo training on EFB usage through a combination of online learning and on-the-job training. The online portion of training is completed on initial hire and then every 12 months. Many pilots reported that most of the functionality of the EFBs is learned while flying with more experienced pilots or by experimenting with the EFBs on their own.

Using the own-ship position functionality on EFBs for navigation is prohibited at Air Tindi when flying above 80 knots unless the aircraft is equipped with a Garmin Flight Stream 210.Air Tindi Ltd., Flight Operations Manual, Edition 4: Version 7 (09 December 2022), section 13.19.2: Preflight Procedures, p. 13-19. At the time of the occurrence, all of Air Tindi’s Twin Otters were equipped with Garmin Flight Stream 210 devices.

Guidance for the usage of the EFB within the FOM is largely centred around device management (battery level, EFB failures, application management, etc.). The FOM also provides the following instructions on EFB usage during flight operations:

- Climb - During climb, the pilot(s) will monitor the applicable charts and route segments on the EFB.

- Cruise - During the cruise or enroute phase of flight, the EFB will be periodically monitored for route progress. Caution should be taken to avoid long exposure to direct sunlight to reduce risks of overheating. Flight crews will select and review the anticipated arrival and approach procedures for the destination airport, leaving the next needed chart displayed.

- Arrival/Approach - If a published Arrival Procedure is being flown, the pilot(s) will monitor the applicable chart. During the approach phase of flight, the EFB will be monitored and appropriate approach chart displayed. Landscape or Portrait view will be “locked” via the ForeFlight application when necessary.Ibid., section 13.19.4: Flight Operations, p. 13-20.

1.17.10.3 Transport Canada guidance on electronic flight bag usage

TC provides guidance related to the use of EFBs in commercial operations in Advisory Circular (AC) 700-020. ACs are not enforceable regulations but rather represent guidance for air operators on a specific issue. As TC states in its circular, “[t]his AC on its own does not change, create, amend or permit deviations from regulatory requirements, nor does it establish minimum standards.”Transport Canada, Advisory Circular (AC) 700-020: Electronic Flight Bags (Issue 03: 28 March 2018), section 1.0: Introduction, p. 3 of 55, at https://tc.canada.ca/sites/default/files/migrated/ac_700_020___electronic_flight_bags.pdf (last accessed on 01 December 2025).

TC’s AC on EFBs states that “[o]wn-ship functionality should only be used for strategic purposes (e.g., situational awareness) and is not to be used as a tool for surface manoeuvring or airborne navigation.”Ibid., Appendix G: Operational Evaluation at the Corporate/Company Level, Use of Own-Ship Position, EFB Own-Ship Functionality, p. 33, at https://tc.canada.ca/sites/default/files/migrated/ac_700_020___electronic_flight_bags.pdf (last accessed on 01 December 2025).

The AC goes on to establish documentation requirements:

(1) The company’s Standard Operating Procedures shall include the following statement:

“This EFB is not certified as a navigation system. Transport Canada has not assessed the EFB for performance or reliability of the platform hardware or software (including GPS functionality).” [emphasis in original]Ibid., Appendix G: Operational Evaluation at the Corporate/Company Level, Company Documentation Requirements, p. 34, at https://tc.canada.ca/sites/default/files/migrated/ac_700_020___electronic_flight_bags.pdf (last accessed on 01 December 2025).

Neither Air Tindi’s SOPs nor the FOM contained this statement.

1.17.11 Controlled flight into terrain training at Air Tindi Ltd.

Controlled flight into terrain (CFIT)“occurs when an airworthy aircraft under the control of the flight crew is flown unintentionally into terrain, obstacles or water, usually with no prior awareness by the crew.”Flight Safety Foundation, “Controlled Flight Into Terrain (CFIT)”, at https://flightsafety.org/toolkits-resources/past-safety-initiatives/controlled-flight-into-terrain-cfit/ (last accessed on 02 December 2025).

The Commercial Air Services Standards require companies operating under CARs Subpart 703 and conducting IFR flights or night VFR flights to provide training on the avoidance of CFIT. This training must include the following topics:

(i) factors that may lead to CFIT accidents and incidents,

(ii) operational characteristics, capabilities, and limitations of GPWS [ground proximity warning system] (if applicable),

(iii) CFIT prevention strategies,

(iv) methods of improving situational awareness, and

(v) escape manoeuvre techniques and profiles applicable to the aeroplane type;Transport Canada, Commercial Air Service Standards, Standard 723: Air Taxi - Aeroplanes, Division VIII: Training, paragraph 723.98(29)(a): Controlled Flight into Terrain (CFIT) Avoidance Training.

Air Tindi provides this training in the form of an online course, which both the captain and the FO had completed in January and April 2023, respectively. The training includes all subjects that are required by the CARs.

The company also provides guidance in its FOM for situations when pilots flying VFR encounter deteriorating weather or whiteout conditions. The guidance states that pilots are required to conduct a 180-degree turn using the flight instruments while ensuring that no altitude is lost in the process. Pilots are further told to not be tempted to descend to a lower altitude to continue flying VFR because this would dramatically increase the risk of CFIT.Air Tindi Ltd., Flight Operations Manual, Edition 4: Version 7 (09 December 2022), section 13.48: Specialty Operations, p. 13-56.

1.17.12 Organizational safety culture

1.17.12.1 General

Safety culture established in complex organizations is recognized as adaptive, evolving “gradually in response to local conditions, past events, the character of the leadership and the mood of the workforce.”J. Reason, ”Achieving a safe culture: Theory and practice”, Work & Stress, Vol. 12, No. 3 (1998), pp. 293-306. As a determinant of how people behave day-to-day, safety culture was defined as “the ‘engine’ that drives the system toward the goal of sustaining maximum resistance toward its operational hazards regardless of the leadership’s personality or [economic] concerns [faced by the industry].”Ibid. As a subcomponent in complex organizations, smaller groups of people who operate unique technology or who by design perform independently of the wider organization reside within a subculture, which is characteristically marked by a set of unique beliefs and interests related to safety.

Safety culture tacitly communicates expectations to new and existing members of the organization, affecting both how the work is accomplished and how fully members participate in an organization’s processes.

Safety culture is the way safety is perceived, valued, and prioritized in an organization. A positive and active safety culture reflects the actual commitment to safe operations at all levels (i.e., the vertical integration of information) in the organization. Safety culture has also been described as “how an organization behaves when no one is watching”V. Aslan, et al., “Safety culture assessment and implementation framework to enhance maritime safety”, Transportation Research Procedia, Vol. 14 (2016), pp. 3895-3904. or "the way we do things around here.”Health and Safety Executive (United Kingdom), "Organisational culture: Overview," at https://www.hse.gov.uk/humanfactors/topics/culture.htm (last accessed on 23 September 2025). The organization’s safety culture is influenced by the values, attitudes, and behaviours of the stakeholders.

Establishing a positive safety cultureThere are several different ways to describe the safety culture in an organization. Terms such as “healthy” or “positive” safety culture are often used interchangeably, as are an “unhealthy” or “negative” safety culture. The TSB prefers to describe safety culture as either positive or negative. has many challenges; however, it is a necessary first step in creating the values, attitudes, and behaviours required for air operators to effectively manage the risks associated with their operations. These efforts and investments will eventually lead to a positive safety culture where unsafe practices are seen as unacceptable by all stakeholders and risks are managed to a level as low as reasonably practicable, improving the management of operational hazards.

The strength of an organization’s safety culture starts at the top and is characterized by proactive processes to identify, assess, and mitigate operational risks. If unsafe conditions are not identified, are allowed to persist or are not effectively prioritized by the air operator, an increased acceptance of such risks can result at all levels of the organization, reducing the effectiveness of the air operator’s SMS and its safety performance. The hierarchy of influences on the way work is accomplished in an organization has been described as the “4 Ps:”

- Philosophy: An organization’s philosophy provides a broad specification for how it wants to operate and it communicates values throughout the organization.

- Policies: An organization’s policies represent broad specifications of how management expects tasks to be carried out.

- Procedures: An organization’s procedures dictate the specific steps an individual should take to accomplish a task. They operationalize the philosophy and policies by indicating how work will be carried out.

- Practices: An organization’s practices represent what actually happens in day-to-day operations. In an ideal world, practices and procedures would be identical. However, in reality, practices may differ from procedures for any one of a number of reasons.A. Degani and E. L. Weiner, On the Design of Flight-Deck Procedures, NASA Contractor Report 177642 (NASA Ames Research Center: June 1994), p.p. 5-8, at https://ntrs.nasa.gov/api/citations/19940029437/downloads/19940029437.pdf (last accessed on 03 December 2025).

One measure of a positive safety culture could be an alignment across the 4 Ps and efforts to identify any gaps and continuously improve. If the 4 Ps are not focused on safety and are not aligned to achieve the higher-level goal of safe operations, this may indicate that a negative safety culture is present in an organization.

1.17.12.2 Safety culture at Air Tindi Ltd.

According to Air Tindi’s safety policy, Air Tindi is committed to safe, sustainable air transportation, with a focus on a positive safety culture and environmental protection. Through its SMS, Air Tindi encourages all personnel to prioritize health, safety, environment, and quality in their actions, aiming to prevent workplace hazards and ensure well-being. Employees are expected to visibly demonstrate leadership in matters of health, safety, environment, and quality, integrating company values into all activities and adhering to regulations and standards.Air Tindi Ltd., Flight Operations Manual, Edition 4: Version 7 (09 December 2022), section 2.2: Safety Policy, p. 2-2.

The investigation determined that pilots at Air Tindi demonstrated a goal-oriented attitude toward decision making and took great pride in completing their flights in challenging operational environments and generally accepted deviation from published procedures. The investigation also determined that the FOs at Air Tindi revere the experienced off-strip captains and hold them in high regard and may sometimes succumb to the halo effectAs outlined by Britannica, at https://www.britannica.com/science/halo-effect (last accessed on 23 September 2025), the halo effect is a cognitive bias in which an impression formed from a single trait or characteristic is allowed to influence multiple judgments or ratings of unrelated factors. In this instance, the junior FO’s way of looking up to the senior captain likely affected his judgment on the safety of conducting VFR procedures in IMC. during VFR flights in inclement weather. The FOs are generally very new to the aviation industry and often rely on the captains to determine what are acceptable practices in the organization and the industry. The FOs would not voice concerns about unsafe practices such as flying VFR in IMC to the captains because there was a perceived notion that “this is how it’s done” when flying in the north.

The SMS at Air Tindi is used to report operational occurrences that affected the flight but is generally not used to identify possible safety deficiencies. As in a previous Air Tindi occurrence,TSB Air Transportation Safety Investigation Report A21W0098, section 1.18.2. the investigation into the current occurrence did not identify any SMS reports relating to unsafe practices, despite these practices being identified by every pilot interviewed during the investigation. The investigation found that pilots who experienced deviations from company SOPs or from published procedures tended to talk informally to the senior captains rather than use the SMS.

These conclusions are consistent with previous TSB aviation transportation safety investigation reportsTSB aviation transportation safety investigation reports A21W0098, A19W0015, A14W0181, A11W0151, and A05W0127. on Air Tindi accidents as well as with Air Tindi’s internal investigation of both this accidentAir Tindi Ltd., DHC-6 | C-GMAS Controlled Flight into Terrain (CFIT), Report Number 5142364, Edition 1, Version 1 (16 February 2024). and its previous accident involving a Twin Otter.Air Tindi Ltd., TIN223 / C-GNPS Aircraft Accident, Initial Report for Issue #5106973 (05 November 2021).

The Air Tindi investigation into this current occurrence noted that the flight crew demonstrated a determined, can-do attitude typical of its personnel, continuing to seek ways to reach their destination despite deteriorating conditions. Because the company operates in challenging environments, it relies on highly experienced captains to manage these challenges, while FOs, who are often new to commercial aviation, learn on the job under the guidance of their captains. Given that FOs do not have the years of specialized experience and training that the captains possess, they also rely on the captains to inform them of the varied threats faced during flight operations.

The acceptance of deviations from procedures and insufficient correction of company culture was also identified in Air Tindi’s internal investigation of a previous accident,Ibid. in which a Twin Otter departed without sufficient fuel to complete the flight resulting in fuel starvation and landing off-airport.

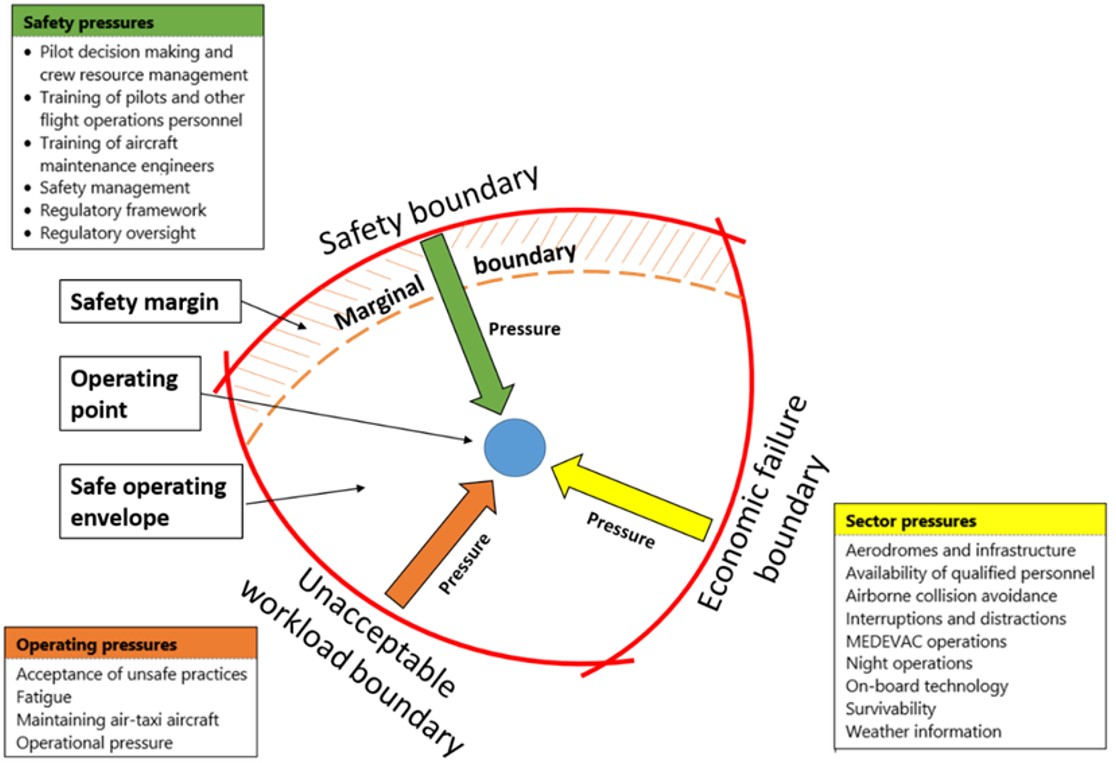

1.17.12.2.1 Acceptance of unsafe practices

In the course of an organization’s activities, unsafe practices may be introduced when personnel work to accomplish goals. These unsafe practices may gradually become accepted as part of the job—in an undetected drift from safe practices—and eventually be taught to newcomers, perpetuating their use. Because these unsafe practices continue with no negative outcomes or often with positive outcomes, such as successful flights or satisfied customers, they may become the norm. Examples of unsafe practices include flying overweight, flying with inadequate fuel reserves, not recording defects in aircraft logs, and “pushing the weather.”