Parametric rolling

What is parametric rolling?

Parametric rolling (PR) is a complex phenomenon that occurs when a vessel experiences the sudden onset of large, violent rolls from side-to-side. It has been recognized as a problem for more than half a century. While it mainly affects modern container vessels and car carriers, PR may occur with other types of vessels as well.

How is parametric rolling caused?

As a vessel moves through the ocean, it naturally rolls from side-to-side. As it encounters waves, the shape and volume of the underwater part of the hull varies between being larger, when the vessel is in a wave trough, and smaller, when on a peak.

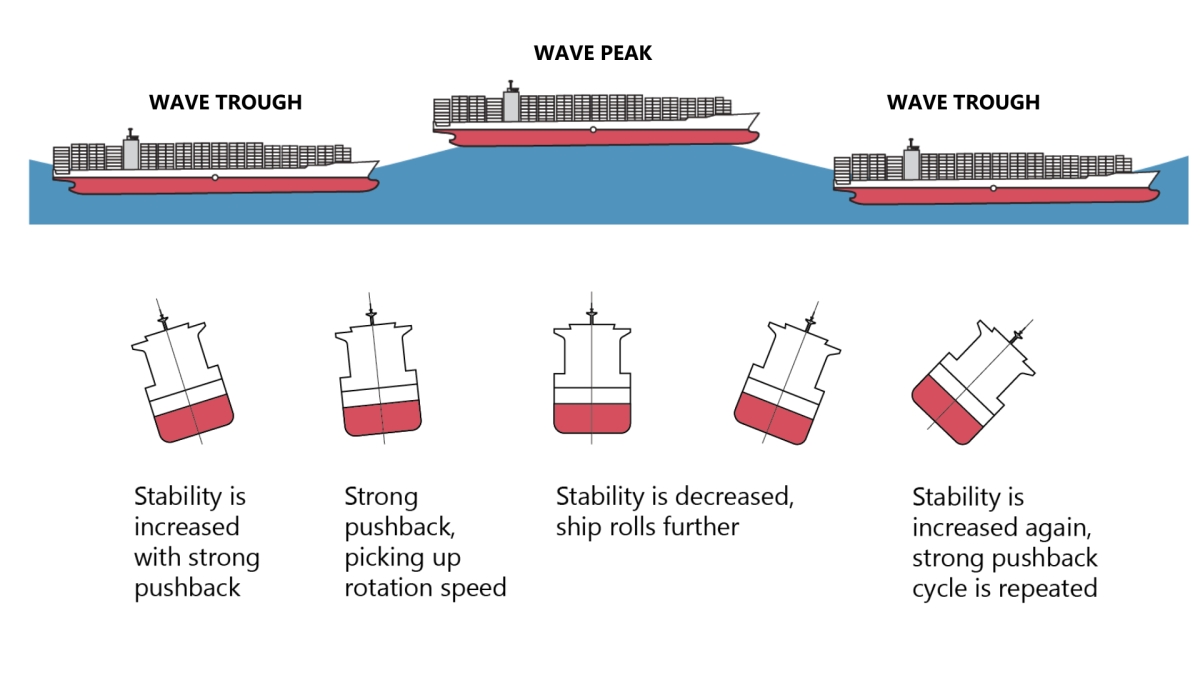

This is depicted in the diagram below – on the left, the vessel is in a wave trough; in the middle, it’s on a peak; and on the right it’s in a trough again. The vessel is most stable when in a wave trough. This means that when the vessel rolls naturally to one side and it’s in a trough (below left in the diagram) at the same time, the forces pushing it back towards the other side are stronger than normal. If the vessel finds itself on a wave peak as it reaches upright (below centre in the diagram), it is then at its least stable position. This causes it to roll over to a larger angle on the other side (below right in the diagram). If this large angle coincides with another wave trough, those strong forces are generated again, pushing the vessel violently back towards the first side, repeating the cycle in the opposite direction (right to left).

For this process to initiate and continue, the rhythm of the vessel’s natural roll motion needs to coincide with the rhythm of the wave encounters. Container vessels like the ZIM Kingston are particularly vulnerable to these rolling motions because the change in underwater hull surface between wave troughs and wave peaks is more drastic than for other vesse types, such as tankers.

Other factors that need to be considered and interact in the “right way” for PR to initiate include:

- the way the vessel is loaded;

- the vessel’s speed;

- the angle at which the vessel is crossing the waves; and

- the sea conditions (the size and shape of the waves).

This type of rolling motion occurs quickly and may only last a short time, but it can lead to dangerous situations for the vessel and its crew and result in cargo damage, loss of containers and, in extreme cases, capsizing of the ship.

To see what parametric rolling looks like, watch this video showing the model testing of the ZIM Kingston (M21P0297) that was done as part of the investigation.

How common is parametric rolling?

Parametric rolling is generally not reported unless there is a significant consequence, such as equipment failure and the loss of containers as in the case of the ZIM Kingston, or significant injuries. It is also possible that occurrences of heavy rolling are not examined or analyzed to confirm whether or not they are actually linked to PR.

The conditions required for PR to start are very common. The size and shape of modern container vessels, which have narrow hulls that widen into large decks, are particularly vulnerable to this rolling effect. These vessels are travelling the world’s oceans and so are exposed to a wide range of sea conditions, including those that could initiate PR.

How do you avoid, or navigate through parametric rolling

As a vessel can go into PR very suddenly, it is important to recognize the early warning signs; and have the tools and procedures in place to forecast and continuously monitor the sea conditions. The most common way to avoid PR is by changing the direction and/or speed of the vessel. These same actions should be taken if PR has begun; however, once it starts, it may be too late to avoid the negative consequences.

There are tools available to seafarers to help evaluate the risk of PR, but none are mandatory. The International Maritime Organization has recently published a new set of interim guidelines that will minimize the risk of PR and will provide a consistent approach to address risk across the international shipping industry. However, these guidelines have not been finalized, and until such time, seafarers and the environment continue to be at risk.

Common factors identified in occurrences related to parametric rolling

Internationally, there have been several investigations and studies into container loss occurrences that involved PR. These reports identify several common factors associated with the monitoring and mitigation of risk associated with PR events on container vessels:

Occurrence vessel name and investigating organization | Year of occurrence | Factors related to monitoring and mitigation of PR risk common to these occurrences | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

Inadequate information and tools | Inadequate procedures | Inadequate training and awareness | ||

| Maersk Essen, Danish Maritime Accident Investigation BoardDanish Maritime Accident Investigation Board, “Maersk Essen: Marine Accident Report on Loss of Cargo, 16 January 2021” | 2021 | Yes | Yes | Not a factor |

| ONE Apus, Japan Transport Safety BoardJapan Transport Safety Board, “Marine Accident Investigation Report, Container Ship ONE APUS, 2020” | 2020 | Yes | Not a factor | Yes |

| CMA CGM G. Washington, UK Marine Accident Investigation BranchUK Marine Accident Investigation Branch, “Report on the investigation into the loss of 137 containers from the container ship CMA CGM G. Washington in the North Pacific Ocean on 20 January 2018” | 2018 | Not a factor | Yes | Yes |

| Svendborg Maersk, Danish Maritime Accident Investigation BoardDanish Maritime Accident Investigation Board, “Svendborg Maersk: Heavy Weather Damage on 14 February 2014” | 2014 | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| P&O Nedlloyd Genoa, UK Marine Accident Investigation BranchUK Marine Accident Investigation Branch, “Report on the investigation of the loss of cargo containers overboard from P&O Nedlloyd Genoa, North Atlantic Ocean, 27 January 2006” | 2006 | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| APL China, Marine Technology and SNAME NewsW. N. France, M. Levadou, T. W. Treakle et al., “An Investigation of Head-Sea Parametric Rolling and its Influence on Container Lashing Systems,” Marine Technology and SNAME News, Vol. 40, No. 1 (01 January 2003) pp. 1–19. APL China, October 1998. | 1998 | No | Yes | Yes |